In the midst of the largest global health crisis in decades, the United States has halted all payments to the Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO). At a press conference at the White House on April 14, 2020, President Donald Trump said that the WHO had failed in its “basic duty and must be held accountable”. He went on to say that the organization had backed China’s “disinformation” about the virus, likely leading to a wider outbreak of the virus than would have otherwise been the case.

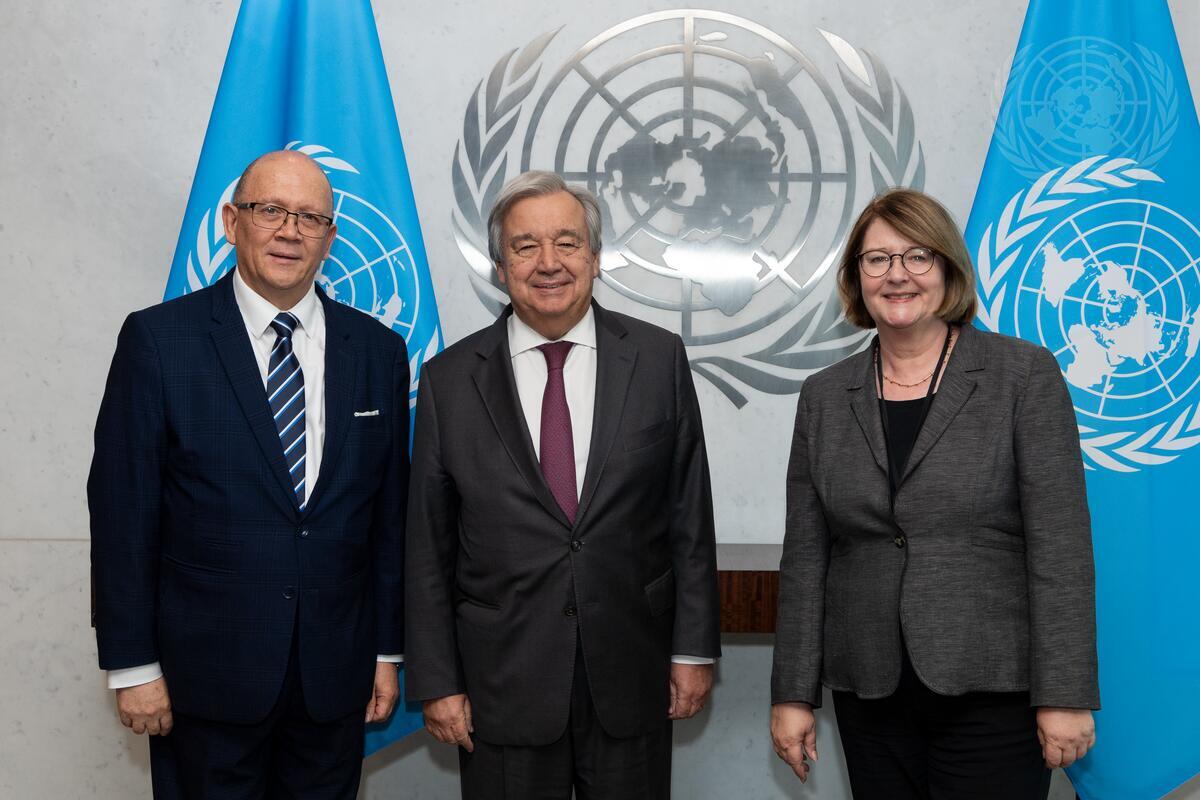

The US contributed more than $400 million to the WHO in 2019, making it the organization’s biggest donor, accounting for some 15% of the total budget. While countries allied with the US such as Australia, Taiwan, Japan, and India supported the move, UN Secretary-General António Guterres, sharply criticized the US government’s decision. Now, in the middle of the crisis, is “not the time” to reduce the organization’s resources, he said. The WHO had only recently requested an additional $1 billion to support the fight against the coronavirus. Guterres went on to say that the WHO is “absolutely critical” for the eradication of COVID-19. Once the crisis is over, it is time to assess the emergence and spread of the virus as well as successes and failures in combating it.

Trump is not alone in his criticism of the WHO and the Chinese influence on the organization in the current crisis, but also with China’s actions. Research by the Canadian organization CitizenLab has shown that Chinese social media began censoring content related to the disease in the early stages of the epidemic. Indications of the danger of the coronavirus were ignored and covered up. Whistle-blowers were silenced. As recently as 24 March 2020, Reporters Without Borders called on the Chinese government to finally allow criticism of its handling of the coronavirus in the face of its continuing crackdown on opinions critical of the Chinese government’s management of the crisis.

Contrary to the WHO’s own claims, the Chinese government had in fact not shown transparency towards the WHO. As early as November 2019, cases of a previously unknown respiratory condition had appeared in the city of Wuhan. The Chinese authorities did not report these to the WHO until December 31, 2019. According to research by the Associated Press, on January 14, 2020 the head of China’s highest health authority informed other government agencies of the potential for a massive public health crisis caused by the virus, but not the WHO. John Mackenzie, a member of the WHO Emergency Committee for Pneumonia due to the Novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV, described China’s response as “reprehensible”, and accused China of not reporting coronavirus cases quickly enough during the early stages of the outbreak.

Nevertheless, the primary reasons for the current discussions about the role of the WHO are not related to the criticism of its actions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. China’s attempt to expand its influence in international institutions such as the WHO and thereby alter geopolitical power structures has been a target of criticism for quite some time. There is little sympathy for China’s efforts to take on a leading role in international organizations. This is despite the fact that the US in particular has, in recent years, repeatedly made it clear that it questions the value of the UN—and multilateralism as such—favouring instead its nationalist “America First” agenda. The clearest sign of this is the country’s withdrawal (under the Trump administration) from the UN’s Human Rights Council, the cultural organization UNESCO, the Paris Climate Agreement, as well as the Iran nuclear deal.

The criticism of the WHO and the US government’s funding halt come at an inopportune moment. They are evidence firstly of the administration’s misjudgement of the current crisis, and secondly, of an ignorance of the organization’s mandate and the way it functions. The WHO is an intergovernmental organization that can only act within the remit permitted by its member states and other financial backers, according to Anna Holzscheiter, head of the WZB research group Governance for Global Health. The political disputes that take place within the organization mean that “the WHO, with 194 member states, cannot react as decisively, quickly, or in a way that bypasses procedural rules to the unprecedented extent we are seeing today, even in countries with democratic constitutions”.

As important as it is more broadly to criticize the often dysfunctional structures of the UN and its sub-organizations, it is especially important right now to stand behind the organizations that are trying to overcome this great crisis. This is the goal of the Civil Society Statement of 15 April 2020 initiated by members of the Geneva Global Health Hub and other civil society colleagues. The Statement asserts that “it is high time all WHO member states acknowledge and support the immense value of the organization in comprehensively tackling the health challenges ahead of us due to climate change, and other threats, instead of using their own mistakes as an excuse to further weaken the organization’s leading role in safeguarding global health”.

The UN and WHO have key roles to play in addressing the health crisis globally. On the one hand, the WHO, which was founded in 1948, can draw on decades of experience in managing pandemics such as HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s or, more recently, the respiratory disease SARS in 2002–2003, and the swine flu in 2008–2009. With its 194 member states, the WHO is able to coordinate national and international activities in the fight against the spread of COVID-19, such as emergency aid in the event of disasters, cooperation on medicines, vaccines, developing tests, and research. At the same time, the WHO can provide concrete, international recommendations for action, such as quarantine measures or travel restrictions for member states. In addition, the UN Secretary-General is a strong advocate who can make the organization’s concerns heard worldwide, and make further recommendations to help overcome the health crisis. For a recent example of this, see Guterres’s appeal for a global ceasefire.

This is the basis from which reforms to the UN and its organizations such as the WHO should be considered and addressed. As early as 2015, the then managing director of medico international, Thomas Gebauer, complained that management issues existed within the WHO, advocating for the improvement of its structure. One reason for the issues, he said, was the reduction in the WHO’s disease control resources, caused by the fact that health is no longer being seen as a human right, but rather being subordinated to economic interests. In order to restore the institution’s independence, business interests must be systematically controlled. Additionally, changes need to be made to the organization’s financing model.

The WHO Programme Budget for 2020–2021 is $4.8 billion US. In comparison, the 2018 budget of Berlin’s Charité hospital was €1.8 billion. The member states’ compulsory contributions now account for just one fifth of the organization’s budget. These were originally the exclusive source of the WHO’s funding, and are vitally important for its work. The contributions have fallen continuously since the 1980s, when member states (beginning with the US under the Reagan administration) started to withhold contributions. In 1993, the US managed to push through a freeze on compulsory contribution levels. According to the Switzerland/UN correspondent for the tageszeitung newspaper Andreas Zumach, this ongoing “phase of financial coercion” has turned the UN and its organizations into supplicants, a development that was accelerated in 1997 when the then UN Secretary-General, Kofi Anan opened the financially stricken UN to private financing. Since then, four-fifths of the WHO’s funding has depended on voluntary, interest-driven contributions by member states and payments by private foundations and companies that are mostly earmarked for specific programmes. Corporate donors have mostly been pharmaceutical companies attempting to influence the WHO’s policy decisions. In 2012 and 2013, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation moved past the US government to become the WHO’s largest donor. This had consequences for the WHO’s programme, which moved away from strengthening public health systems to focus on a few diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria, against which vaccinations or mosquito nets can be employed for quick and cost-effective results.

The current crisis can only be contained by massive, worldwide investment in the health sector that is coordinated by the WHO and supported by the international community. This must include the Global South, where the course of the pandemic is yet to unfold. In contrast to national governments, the WHO constantly foregrounds the global dimensions of the crisis, particularly because the countries of the Global South have significantly weaker health systems and wholly lack the financial resources that the North is currently using to cope with the crisis. Here, the international community must step up to help. In March 2020, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were already calling for deferment of the poorest countries’ debt. In mid-April, the G20 agreed to defer all interest and debt payments for the 77 poorest countries from May to December 2020. In the medium and long term, however, the goal must be preventing other epidemics, such as Ebola, and much more. In order to manage health crises such as the current one, the independence of the WHO must be restored. A massive increase in the level of compulsory contributions, which is currently far too low, is central to this. According to Bread for the World, in view of the uncertain course of the development aid policies of major donors like the US—as seen in the current suspension of payments by the US government—alternative models such as gradual increases should also be considered.

However, this will require the majority of member states to rethink their positions. As recently as 2016, former WHO Director-General Margret Chan had called for a 10% increase in compulsory contributions, representing a departure from the “zero nominal growth policy”. Chan’s efforts were unsuccessful, even though she made it extremely clear that without an increase certain program areas would have to be either cut back or cancelled altogether. An important reason for the rejection seemed to be member states’ lack of ownership. They did not see the benefits of WHO’s work for their countries perceiving the WHO as a service provider, rather than as an organization which they, as member states, were part of.

The stagnation and reduction of compulsory contributions to the WHO and a lack of ownership further contributed to its weakening, as more and more health-related activities migrated to other institutions. First they moved to other UN agencies such as UNICEF, and since 1996 to UNAIDS. Later they went to public-private partnerships such as the Global Fund and the Global Alliance for Vaccines, Gavi. Most recently they have migrated to multi-stakeholder initiatives. According to Canadian scientist Anne-Emanuelle Birnden, such arrangements, which have been supported by the World Economic Forum and even the UN, have ensured “that the WHO is just one partner among many and no longer—as is its actual mandate—the coordinating authority for promoting global health and protecting health as a “fundamental right”.

If the WHO is to fulfil its founding mission of attaining the highest possible level of health by all peoples, its role and authority as the single, central, democratically legitimated authority on global health issues must be strengthened in the long term. Only in this way can the WHO not only coordinate and moderate in the future, but also regain its leading role in the global health sector. It is crucial for the WHO to return to the organizational goals outlined in its constitution—namely to contribute to the overall improvement of living conditions on the basis of sound, independent scientific knowledge.

The developments of past decades that need to be reversed are not just financial in nature. The effectiveness and success of WHO activities should be evaluated on the basis of whether they contribute to greater health equity, and not whether they conform to the logic of the market. The notion of health as a fundamental right must be defended and put into practice. This implies democratic negotiation processes and a corresponding change in thinking on the part of the member states. These must no longer regard health care as an issue to be regulated by the market economy, but rather work towards the creation of a health care system based on solidarity, in which health care is viewed as a political, economic, and social duty.

As medico international called for in 2018 on the 40th anniversary of the Declaration of Alma-Ata (the final document of the WHO’s 1978 conference in Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, and as the WHO itself reiterated in its World Health Report 2008, the organization must return to the principles of so-called “Primary Health Care” codified in the declaration. This means, as stated in the Declaration of Alma Ata, recognizing health care as a “fundamental human right” and that “the attainment of the highest possible level of health is an extremely important world-wide social goal whose realization requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector”. This also means putting the health system back into public hands, which is to say reversing neoliberal structural reforms that have been put in place since the 1970s, as well as democratizing the system. And this needs to occur at all levels: both at the level of workers, for example through supporting campaigns for wage increases and increases in hospital staffing through social alliances and referendum campaigns; and at the level of the health care system itself, for example through the democratization of the nominally still existent self-administration of the health care system, through the participation of patients in decisions and developments in the health care system, and through a health insurance system based on the principles of solidarity and the direct payment of medical costs by insurance companies, but also through a democratization of medicine as such.

The pressure for change must come from below, from well-organized and tenacious forces within civil society. At the same time, according to the new managing director of medico international, Christian Weis, major questions will have to be discussed anew and lessons learned from this pandemic. Which institutions, companies, and also professions are truly necessary for the functioning of society? What public resources and institutions need to be protected and rebuilt—including those that lie beyond the economic sector? What is crucial for maintaining and strengthening a diverse, democratic society and must therefore be kept alive now in these times of crisis? At the same time, according to Anna Holzscheiter, the COVID-19 pandemic must be situated within a broader context, as it is not only a health crisis but also a “pandemic of global inequality”, to which billions of people are being exposed without protection. This is especially the case in poorer countries and regions where other infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV are already widespread. The WHO highlights immediately relevant health topics in this context, such as poor working conditions, the migration of health personnel, and gender inequality in the health sector. It collects important data and circulates them. This is evidenced in publications such as the WHO State of the World’s Nursing Report on the worldwide state of health care personnel, which was released in early April 2020.

There is a need for a debate on the effectiveness of multilateralism, its organizations and instruments, both in relation to the current health crisis and the issues of climate change and military conflicts. This is particularly important now that, given the tensions between China and the USA described at the outset, the COVID-19 pandemic has hardly reduced the likelihood of a confrontation between these two countries.

Eva Wuchold is Program Director Social Rights in the RLS Office Geneva.

Translated by Jordan Schnee and Joel Scott for Gegensatz Translation Collective.