This article is part of our series “On the Precipice: A Progressive Agenda in the Biden Era.” Download a PDF of the full series here.

Among the challenges President-elect Joe Biden will face on assuming power will be maintaining the illusion that the United States and other nuclear weapons states are committed to the obligation under Article VI of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty article VI obligation to engage in “good faith” negotiations for the complete elimination of their nuclear arsenals.

Without serious and credible steps toward fulfilment of that obligation, the world will face both the increasing danger of nuclear war and increasing numbers of nations opting to equalize the balance of terror by creating their own nuclear arsenals.

Biden comes to office in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s devastating assaults on the world’s nuclear arms control architecture, developed through challenging negotiations over the past 60 years. He also inherits the 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, which reiterated the U.S. first strike nuclear war fighting doctrine, called for the deployment of more usable battlefield nuclear weapons, increased the circumstances in which nuclear weapons can be used—including in response to cyber-attacks—and increased spending for nuclear weapons and their delivery systems as part of a 30-year, $2 trillion nuclear weapons “modernization” program.

Biden is no nuclear weapons abolitionist. What arms control and disarmament measures he may wish to pursue will be constrained by the need to spend of his political capital on defending and preserving U.S. constitutional democracy from the attacks of right-wing white supremacist forces, containing the COVID-19 pandemic and revitalizing the country’s devastated economy.

His nuclear weapons priority during his first weeks in office will be negotiating a five-year extension of the New START Treaty with Russia before the Treaty’s expiration in February. The second and more challenging priority will be rejoining the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the United Nations agreement which capped Iran’s nuclear program. Trump violated the agreement by unilaterally withdrawing from it.

Trump also added a major complication to future U.S.-Iranian negotiations by celebrating the Israeli killing of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, Iran’s leading nuclear scientist. The assassination has reinforced the hand of Iranian conservatives who oppose revitalization of the JCPOA, and who will likely come to power in Iran’s spring election. President Biden will thus have to restore trust and reach an agreement with Iran during his first two months in office if the agreement is to be saved.

While Biden has signaled an interest in reducing U.S. nuclear weapons spending, he remains committed to most of the $2 trillion U.S. nuclear upgrade. Possible cuts could come in the $85 billion program to replace the country’s 400 highly vulnerable “use them or lose them” land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and to future deployment of the destabilizing standoff cruise missiles which are adding fuel to the arms races with Russia and China.

As we approach the August 2021 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference (RevCon) at the United Nations, Biden’s nuclear commitments are not the only obstacles to progress toward fulfillment of its Article VI commitment to “good faith” negotiations for the complete elimination of the world’s nuclear weapons. With the relative decline of its conventional forces and pressed by NATO forces along its borders, Russia has increased its reliance on nuclear weapons, and deployed a new generation of the omnicidal weapons. France, the U.K., India, Pakistan and Israel are each upgrading their nuclear arsenals. North Korea is augmenting its arsenal, which can reach targets including Seoul, Tokyo, Guam and the United States. And, in the face of the U.S. nuclear buildup, China is adding to its deterrent arsenal to ensure its second-strike capacity.

All of this serves to undermine the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), and increases the probability that other nations will withdraw from the pact that they experience as enforcing the double standards of a discriminatory nuclear disorder and will develop nuclear arsenals of their own.

The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty

The NPT is the endangered cornerstone of the arms control architecture and the foundation of nuclear disarmament diplomacy. It was initially designed to prevent nuclear weapons proliferation and to return humanity to a nuclear weapons-free world. The treaty entered into force in 1970, with 191 countries now legally obligated to fulfill their NPT obligations. In essence, the Treaty is a three-pillared bargain between the nuclear powers and non-nuclear weapons states: Non-nuclear weapons states renounce ever developing or possessing nuclear weapons. In exchange, the nuclear powers guaranteed them access to nuclear power for peaceful purposes.

A major flaw in the bargain is Article IV, the second pillar of the Treaty, which guarantees non-nuclear weapons states the inalienable right to generate nuclear power for peaceful purposes. Consequently, the world now has 440 nuclear power plants emitting poisonous radiation. With long-term provisions for safe storage of this nuclear waste yet to be devised, communities and the environment across the planet are held hostage to deadly contamination.

In addition, India, and Pakistan, which never signed the NPT, and North Korea which did, used their nuclear power programs as cover to develop their nuclear weapons capabilities. Nuclear power programs in countries including Iran, Japan, South Korea and Brazil have raised concerns about possible future breakouts from the Treaty.

The third and most consistently violated pillar of the NPT is Article VI. It requires all parties to the Treaty “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament”. Additional treaty provisions mandated that review conferences be held every five years to ensure that the treaty is being implemented. It further mandated that 25 years after the treaty came into force a conference was to be held to determine if the treaty should be extended or continued indefinitely.

Despite fears in the early 1960s that 20 or more nations could soon develop nuclear weapons, horizontal proliferation has been limited to India, Pakistan, Israel and South Africa (which later eliminated its nuclear arsenal).

Commitments Made and Broken Leading to the TPNW

By the time of the 1995 review and extension conference, there were growing doubts that it would ever be fully implemented. Despite the end of the Cold War, the U.S. had 10,577 nuclear weapons and Russian had 27,000. India, not a party to the Treaty, had exploded an “atomic device” in 1974. Mordechai Vanunu was isolated in an Israeli prison cell after revealing photographs confirming the existence of Israel’s nuclear program in 1986. And, in 1991 the U.S. and Britain had explicitly threatened Iraq with nuclear attacks in the weeks preceding the Gulf War.

Due to these circumstances, there was concern that the Treaty would collapse, but a compromise was achieved. In exchange for the indefinite extension of the Treaty, the nuclear powers renewed their commitments to Article VI and agreed that Preparatory Committee meetings would be held prior to future Review Conferences. The declaration mandated universalization of the Treaty to bring India, Pakistan and Israel into the NPT order, negotiation of a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and Fissile Material Cut Off Treaty. It also reaffirmed the value of nuclear weapons free zones and required that nuclear weapons states commit to not attacking the non-nuclear weapons states with nuclear weapons. Crucial to the agreement to extend the Treaty was the commitment to work for the establishment Middle East nuclear weapons-free zone.

It’s been downhill since then. In 2005, during the George W. Bush administration, the nuclear powers delayed agreement on an agenda, leaving little time for meaningful negotiations. Only one and a half of the 2010 RevCon’s 13 agreed steps have been implemented. And in 2015, the Review Conference collapsed in failure when the Obama Administration refused to commit to participating in an initial conference to develop the Middle East Nuclear Weapons Free Zone mandated in 1995 to extend the Treaty.

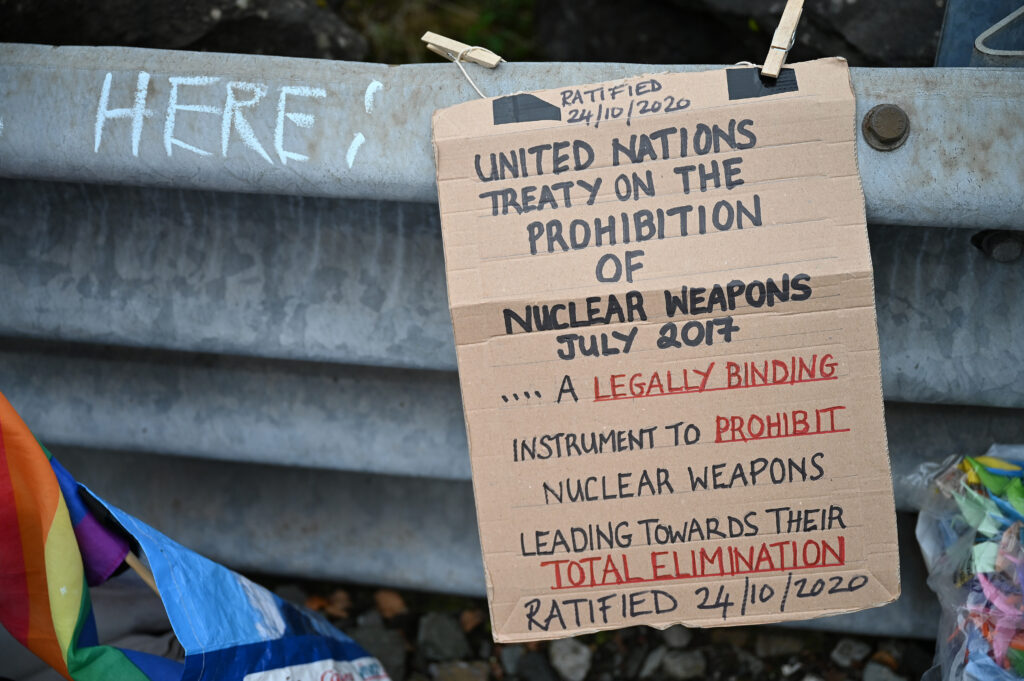

It was against this background, that in 2017, that brought 122 governments, international organizations, and civil society representatives together to negotiate the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Having secured the necessary ratifications, the Treaty will enter into force in January 2022. The TPNW, which serves to further undermine the legitimacy of nuclear weapons, is designed to reinforce the NPT.

It prohibits the development, production, manufacture, acquisition, possession, stockpiling, transfer, stationing, installation and threat of use of nuclear weapons. Among its most important articles are those that forbid non-nuclear weapon states to assist the nuclear activities of the nuclear powers, for example refueling nuclear capable bombers; the mandate to assist nuclear weapons victims, and the requirement that Treaty nations “encourage States not party to this Treaty to sign, ratify, accept, approve or accede to the Treaty.” “Encouragement” could take many, potentially coercive, forms.

None of the nuclear weapons states have signed the TPNW, and they are unified in their opposition to the Treaty.

What to Expect from the 2021 Review Conference

As we approach this August’s Review Conference, twice postponed due to the pandemic, expectations are low for meaningful breakthroughs. This could further undermine the Treaty. Activists associated with the International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapon will certainly come to New York to press diplomats for additional TPNW signatures and ratification.

Fears that a failed Review Conference will spur further nuclear weapons proliferation is a source of concern to the Biden Administration and other nuclear powers. Hopes have been expressed that extension of the New START Treaty and possibly the revitalization of the JCPOA could provide sufficient goodwill to elicit cooperation and agreement on a final declaration. Although there have been no indications from the Biden camp that it will do so, it has been suggested that a U.S. no-first use declaration at the conference, even before it could be codified in the Administration’s nuclear posture review, would inspire and transform the diplomatic environment.

That said, much of the world remains outraged by the failure to implement Article VI, to fulfill the 13 steps of the 2010 RevCon, and by the increasing dangers of the great and lesser powers’ nuclear arms races. There also remains the possibility that, like President Obama, President Biden will continue providing cover for Israel’s ostensibly secret nuclear arsenal. Should it refuse to commit to supporting negotiations for a Middle East Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, the Review Conference could fail, further weakening the NPT order.

One thing remains certain. With the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Doomsday clock warning that humanity is 100 seconds from unimaginable catastrophe, diplomats and international civil society activists committed to ensuring human survival will descend on New York in August to press for meaningful action to eliminate the dangers of nuclear weapons.

Dr. Joseph Gerson is President of the Campaign for Peace, Disarmament and Common Security, Vice-President of the International Peace Bureau, Co-founder of the Committee for a Sane U.S.-China Policy, and author of Empire and the Bomb: How the U.S. Uses Nuclear Weapons to Dominate the World.