This article is part of our series “On the Precipice: A Progressive Agenda in the Biden Era.” Download a PDF of the full series here.

For decades in the United States, the military budget has been sacred for both parties: nothing gets in the way of maintaining U.S. hegemony. While bitter debate may erupt over other forms of federal spending, and any other bill runs the risk of becoming a political football, the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) is usually a drama-free display of bipartisanship followed by a Presidential rubber-stamp.

2020 was different. In the last month of a most atypical year, amid a second spike in the COVID-19 pandemic, and in the aftermath of widespread uprisings for racial justice, President Trump vetoed the NDAA for reasons that were baldly racist. He objected to a symbolic gesture that would rename military bases with Confederate names, and self-servingly, insisted on a provision that would remove legal protections for tech companies from liability over content posted by users on their platforms, so they can no longer censor posts they don’t like—like his own.

For very different reasons, a bipartisan minority of senators led by Senators Bernie Sanders then threatened to hold up the NDAA veto override as collateral in the fight to force a vote on $2,000 stimulus checks to the public. Ultimately, both measures were defeated on New Year’s Day by large majorities in the House and Senate. The Pentagon got its $740 billion budget, and the public missed maximal economic relief amid the ongoing spike in COVID-19 cases.

The NDAA has only been vetoed by a President five times since the first one in 1961, most of them easily resolved quibbles over how particular assets were allocated. The last time was in 2015, when President Barack Obama vetoed the bill in order to lift spending caps on both military and non-military spending, against Republican efforts to only do the former— and his rhetoric was very much in terms of properly funding the military.

One upshot of Trump’s veto is that the military budget is finally being politicized, after many years of stultifying consensus that rendered it untouchable against even symbolic objections. These maneuvers failed this time against bipartisan majorities, but perhaps a process has finally begun of treating the NDAA like any other bill, not a sacred object that must pass at literally any cost.

In microcosm, these two fleeting efforts to stall Pentagon funding reflect alternate tendencies through the Trump years to reckon with a thoroughly, unsustainably militarized global order. On the right, the neoconservative consensus has grown into a reactionary desire to revitalize the racism and exclusionary violence that has been subdued in recent decades but is foundational to the United States, and on the left the progressive movement is fighting to redistribute the vastly unequal wealth within this nation to serve the public good.

With these two diverging paths, the danger is that Biden simply attempts a return to a pre-Trump status quo or—to “build back better” without thoroughly re-evaluating U.S. military policy. But that status quo is what led to Trump and can’t last in an era of ongoing, intensifying crises that demand fundamental shifts in federal budget priorities.

Therefore, an organized left must take stock of strategic cleavages to push for military spending cuts in the near term, and lay the groundwork for major long-term transformation of U.S. policies away from militarism and imperial domination of the rest of the world, and toward social and ecological repair.

Mask Off for the Empire

Rhetorically, Trump confounded many bipartisan norms on military policy, speaking and behaving in contradictory ways. On the 2016 campaign trail, he named the Iraq invasion as “the single worst decision ever made.” and repeatedly criticized George W. Bush for botching the war. He infamously mocked the military service of the late Sen. John McCain, and is since alleged to have frequently disrespected rank-and-file soldiers as “losers” and “suckers”. Yet, through it all he maintained intense popularity among a consistent 40% of the eligible voting population even through the 2020 election.

Trump campaigned in 2016 with a mixed message of criticizing US military adventurism, and moved to withdraw troops stationed in Africa, the Middle East, and Germany — often against bipartisan opposition in Congress. But he never really intended to end the wars. When he talked about ending the wars, he usually meant ending risk to American lives. His “America First” rhetoric wasn’t just skeptical of foreign involvement — it was openly contemptuous of the lives of people from what he allegedly called “shithole countries” of the Global South. Trump launched and celebrated spectacularly belligerent displays of U.S. violence:He authorized troop surges in Iraq, escalated massive drone strikes in Somalia,gleefully dropped the “mother of all bombs” in Afghanistan, and assassinated Iran’s major general Qassim Suleimani in an unprovoked attack, recklessly bringing the U.S. to the brink of war against Iran in early 2020. When confronted about his relationship with a “killer” autocrat like Putin, Trump infamously answered: “We got a lot of killers. What, you think our country is so innocent?”

But previous administrations’ military policies weren’t so substantively different from Trump’s. Yes, Trump more openly aligned with right-wing authoritarian leaders like Modi in India and Netanyahu in Israel,but this just made more explicit the long-established tradition of U.S. relationships with oppressive regimes like Saudi Arabia when convenient for business, especially weapons sales. Trump made explicit what has long been masked by the political class across parties: U.S. military actions often function to enforce the smooth functioning of U.S.-dominated global capitalism. This happens at the expense of the self-determination of people around the world who are subjected to a basically colonial relationship to multinational corporations that profit from exploiting their resources and labor. War itself is an industry, with private contractors profiteering from each new line item for “defense” in the federal budget.

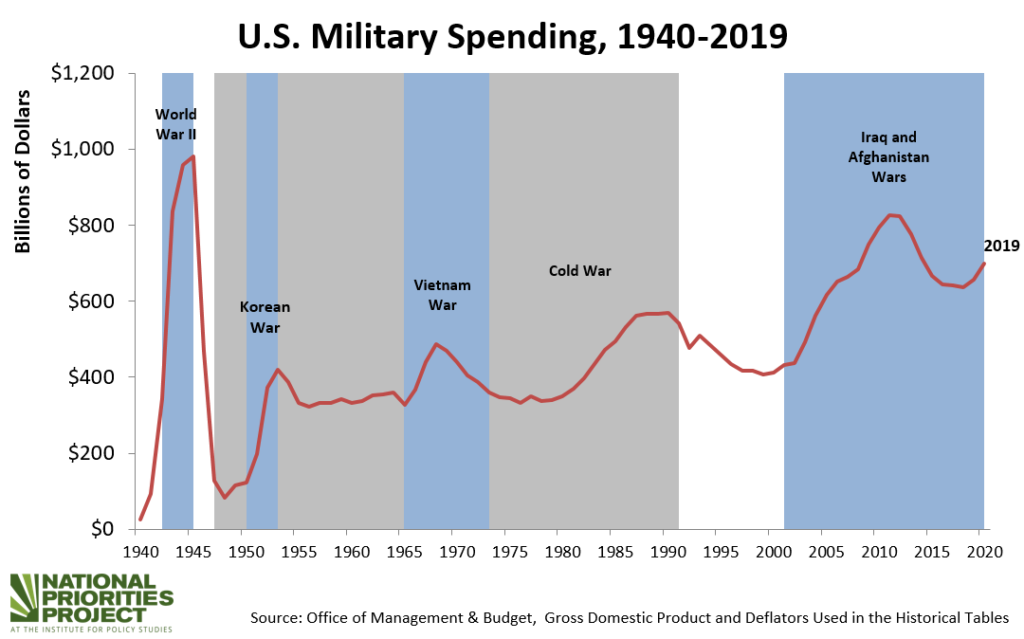

Trump’s rhetoric was openly imperialist about taking other countries’ resources by force. His administration oversaw massive jumps in Pentagon spending in every year of his presidency, increasing almost $100 billion from when he took office in 2017 to when he left four years later. Even while denouncing Trump’s recklessness, most Democrats in Congress voted for these increases to the military budget each year.

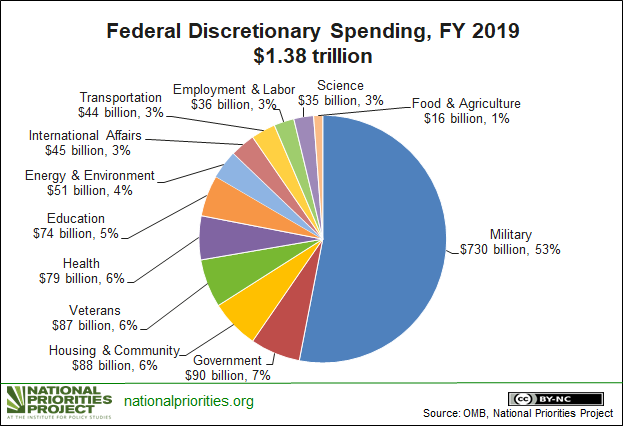

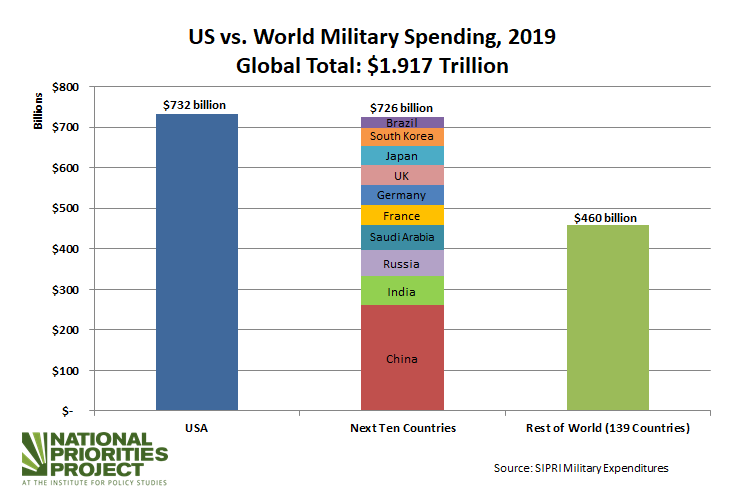

Adjusted for inflation, the current military budget of $740 billion for 2021 is more than at any point in U.S. history since World War II, except at the peak of the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Such an enormous amount is more than the next 10 highest-spending nations combined, making up almost 40% of the entire planet’s military spending. 53% of the discretionary budget allocated by Congress every year—more than all government spending on public health, education, transportation, housing, and clean energy combined—is dedicated to this warmaking.

These trends largely predated Trump. Just about half of the military budget goes to private corporations like Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, who profiteer from lucrative contracts building the machinery of war, while less than a quarter goes to the troops in the form of pay, housing, and benefits. About $150 billion goes toward maintaining over 800 foreign military bases that inflame regional tensions enabling avoidable wars around the world. The endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are providing cover for a $70 billion bump in Pentagon spending, only about half of which is used for those conflicts.

The human costs of all this are incalculable. At least 800,000 people have been killed by direct war violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, and Pakistan, the vast majority of them civilians. Many more have died from the destruction of infrastructure like hospitals, and many more than that have been injured or disabled. And America’s post-9/11 wars have driven at least 37 million people from their homes, creating the greatest human displacement since World War II—comparable to the entire population of Canada, or everyone living in the state of California, becoming refugees.

In many ways, Trump has been an authentic expression of many decades of national spending priorities that privileged massive militarization of borders, police and entire societies around the planet, while facilitating extreme upward transfer of wealth to handfuls of billionaires.

Back to Normal?

The incoming Biden administration has repeatedly indicated its desire for America to “lead the democratic world” again, promising a return to a world order based on liberal interventionism, despite that status quo being tenuous. It remains to be seen how Biden will break with Trump’s decisions on military policy, or whether the transition is largely continuous. “Space Force,” one of Trump’s most outlandish ventures, appears likely to stay. It was budgeted $15 billion for this year— almost enough to end homelessness in the U.S.

Under Obama, the US spread its officially acknowledged wars to seven nations: Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. The US actually had troops in combat to fight “terrorism” in at least 14 nations as of 2018, and is actively engaged in various kinds of “counterterrorism” activity in 80 nations. Many of Biden’s cabinet picks are Obama alumni, part of the democratic administrative state known collectively as The Blob, who are ready to pick up similar roles where they left off four years ago. Some of these people shaped the most militaristic policies of the Obama administration, like secretary of state nominee Tony Blinken with the disastrous intervention in Libya. However, in a difference from Trump, they may at least be compelled to end the disastrous war in Yemen. Others secured notable successes, like deputy secretary of state nominee Wendy Sherman with the Iran nuclear deal, which must be restored for any chance at repairing the havoc wreaked by Trump—and then some.One of the most pressing questions of the transition is whether some of these former Obama officials will update their views in a post-Trump world.

Biden and close advisors send mixed signals about whether the military budget is likely to shrink or expand. Kathleen Hicks, nominated for deputy secretary of defense, has considered the possibility for long-term budget reductions by shifting military priorities to require fewer warships and nuclear weapons. Retired Gen. Lloyd Austin, Biden’s pick for secretary of defense, hasn’t said much publicly about policy preferences, but has been a paid board member of the weapons maker Raytheon, one of the top profiteers from Pentagon contracts. The revolving door with private contractors has long skewed military spending priorities, and indeed many of the Department of Defense (DoD) cabinet picks have direct industry ties. Victoria Nuland, the particularly hawkish nominee for under secretary of state for political affairs, has encouraged “robust defense budgets” and new weapons systems to keep a military edge over Russia.

No matter how key decision-makers feel about it personally, forces within the national security establishment will continue to push reasons for military spending increases. The easiest path forward for administration officials will always be the one of higher spending.

Great Powers Conflict

In late 2018, a report issued by the bipartisan National Defense Strategy Commission called for Congress to approve annual increases of three to five percent in the Pentagon budget above inflation, which could yield almost $1 trillion in military spending by 2024. Among the stated reasons is the specter of a looming “national security emergency” that justifies huge military spending increases, perhaps related to the eruption of open war with China or Russia.

The bipartisan consensus around a militarized threat framing of “Great Powers” conflict, especially against China, has been in the works for many years, and especially intensified after China’s relatively quick economic recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis. The Obama administration began a “pivot to Asia” with a military buildup around the Pacific Ocean and South China Sea in efforts to contain China. That set the groundwork for Trump to further ratchet up tensions, which a National Security Strategy memo in 2017 explained was because of the return of “great power competition,” justifying US military growth.

Anti-China rhetoric has now surpassed the never-ending “War on Terror” as the driving force behind military budget increases from both sides of the aisle, which voted overwhelmingly for higher NDAA topline numbers every year Trump has been in office, and allocated billions specifically to the “Pacific Deterrence Initiative” this year. While Trump’s public statements have xenophobically weaponized the COVID-19 pandemic to scapegoat China for his administration’s own failure to manage a public health response, Biden has at times reinforced this kind of rhetoric as well. The new administration may be less belligerent, but all indications are that Biden’s military and foreign policy cabinet will reinforce the growing push for confrontation.

Top military officials describe China and Russia as “near-peer competitors” to the U.S. that must be confronted, but it’s important to emphasize just how much the U.S. outpaces any other nation with its military footprint. Annual Pentagon spending is almost triple China’s military budget, and over 10 times Russia’s. Compared to the U.S.’ more than 800 overseas military bases, Russia has around 21. China only has one overseas base, in Djibouti. Pentagon sources anxiously speculate that more Chinese overseas military bases are in the works, but even if this is true, the U.S. already has 29 bases in Africa alone. Officials justify the U.S. AFRICOM presence largely to compete with the influence of Russia and China on the continent, but there is little transparency about what role the U.S. military has really played there, and many indications that U.S. intervention is failing to counter terrorism, and may in fact be causing violence to spike. Whatever the perception of China’s interests in projecting its power, it seems as if the military threat is severely overblown, and the U.S. response may be doing more harm than good.

Securitizing the climate crisis

Another factor likely to drive requests for increased military funding is the push to frame the climate crisis as a matter of national security, articulated consistently by John Kerry, President-elect Biden’s nominee for special presidential envoy on climate. It is undoubtedly true that climate change is an immediate threat all over the world, and some regions are already much more vulnerable than others. Societies can be destabilized by climate impacts—the ongoing conflict in Syria, exacerbated by severe drought, is one example.

Planners in the Pentagon have been internally considering the climate crisis through a securitized frame as early as 2004, viewing climate disasters as “threat multipliers” that ultimately demand a militarized “armed lifeboat” response to contain societal unrest. Longer-term analyses and scenario-planning in this vein become truly dystopian. A video used at the Pentagon’s Joint Special Operations University warns of the “unavoidable” need to prepare for “hybrid threats” in megacities all over the world like Lagos or Dhaka, which will require the U.S. military to engage in urban warfare against restive populations.

One 2019 analysis from the U.S. Army War College warns that the U.S. military is “precariously underprepared” for escalating climate crisis, outlining possible future sites of conflict for a new era of endless war. Of course, the proposed solutions include increased funding for combat preparedness in an increasingly diverse and disturbing range of scenarios, like new interventions in highly populated climate-vulnerable nations at risk of mass migration, like Bangladesh. John Kerry’s former think tank, the American Security Project, lays out a vision of militarizing a rapidly melting Arctic ocean to repel Russia— a long time obsession of “war gamers” who fear Russia “winning” the climate crisis.

But why are armed conflict and military intervention a foregone conclusion, rather than pre-emptively building the infrastructure for a green economy that can mitigate future impacts of climate change, and developing much stronger global capacity for diplomacy and real humanitarian interventions? The military itself is a huge polluter — and is often deployed to sustain the fossil fuel industries that destabilize our climate. Simply positioning the Pentagon as a “key player in the war on climate change,” as did military policy advisor Michele Flournoy, without fundamentally reconsidering the role the U.S. military plays in the world, risks ever more militarized quagmires intended as solutions to avoidable conflicts.

Instead of pouring ever more unaccountable resources into DoD agencies for “greening the military,” while allowing the actual causes of climate change to intensify, governments could better use funds to address the root causes of climate crisis in ways aligned with a Green New Deal, which the public can appreciate and directly benefit from in their daily lives.

Wealthy nations like the U.S. are disproportionately responsible for carbon emissions in the atmosphere that are causing the climate crisis, and possess the vast resources needed to adapt, due in part to the ongoing legacy of colonial extraction from societies around the world that are now most vulnerable to and least responsible for climate chaos. Sharing the resources needed to fund mitigation and adaptation efforts abroad is a matter of collective survival, and global justice. A fair share of global climate finance from the United States would approach $680 billion, almost the size of the entire current military budget. And yet under President Barack Obama, U.S. commitments to the global Green Climate Fund (GCF) never exceeded a mere $3 billion. Under Trump, the U.S. withdrew themselves completely from the GCF. If the Biden administration is truly viewing the climate crisis for what it is—the greatest existential threat—then they should signal commitments to strengthening and reimagining the GCF instead of building out the military.

Pandemic Profiteering

On the campaign trail in 2020, Biden promised to use the military’s vast logistical capacity to help contain COVID-19—a reflexive assumption by many policymakers that the U.S. military is the best situated force to deal with any threat. Any notion that the Pentagon should be reliably tasked with pandemic relief should be dispelled by the reality of how its response played out. In the CARES Act, the Pentagon took $1 billion dollars in COVID-19 relief funds that were supposed to go towards making masks and equipment to protect workers from disease— and gave much of it to weapons manufacturers for jet engine parts and other war-making equipment irrelevant to the COVID crisis. Some parts of the military did step up with real support, but these were modest acts amid shameless profiteering from the military-industrial complex, which also lobbied for billions for unnecessary weapons systems from the COVID-19 bailout legislation.

An institution designed for warfare is an inefficient, expensive tool to combat infectious diseases, as was already proven by the Obama administration’s slow and costly militarized response to the Ebola outbreak in 2014. The COVID-19 pandemic has amply demonstrated that civilians need to take control of the military’s resources—not the other way around. The entire budget for the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) for 2020 was $7.7 billion — the total military budget was 100 times larger. The best way to prepare for disease outbreaks, or any other kind of crisis, is not to keep haphazardly funneling resources to a bloated militarized bureaucracy that’s not fit for purpose. The way is to actually fund societal needs like public health.

Openings for the Left

Progressives should be clear-eyed about the incoming administration’s stated priorities thus far. Status quo bias may be strong, especially for those who were also in the Obama administration. But this is a fundamentally different political landscape than in 2008. Perhaps Trump’s poor management of the administrative state, with many career officials quitting or leaving and never being replaced, leaves more room for movement rather than institutional inertia.

It’s possible that Trump’s presidency was accidentally transformational on economic policy, leaving both parties more interested in promoting demand through fiscal aid than policing budget deficits. In a post-COVID world, after multi-trillion-dollar stimulus bills with direct payments to the public, it may be increasingly untenable for politicians to explain that it is simply not possible to pay for nice things. Meanwhile, the Pentagon has repeatedly failed comprehensive audits in recent years, and meets no reasonable standard of fiscal responsibility.

One changing dynamic this year comes from the expiration of budget caps put in place by the Budget Control Act of 2011, giving Congress a big opening to deeply shift priorities away from austerity and the Pentagon in a way that has not been on the table for many years. The arguments to rein in military spending seem increasingly clear, and Americans tend to favor reinvesting for urgent social needs.

Where’s Our Cut?

Last summer, progressives led a push to amend the NDAA with a 10% budget cut—a breakthrough, since this was the first time in decades that Congress seriously considered shifting resources away from the Pentagon budget at all. The amendment failed, but just a few years ago it would have been hard to imagine even 40-50% of the Democratic Caucus in the House and Senate voting to cut the military budget, as they did in 2020. That sets a baseline for a renewed fight this year.

Ten percent of the current budget is a whopping $74 billion, which would be transformative for any number of social priorities, like closing the public school racial funding gap, or creating one million green jobs that pay well enough to transition every fossil fuel worker. This is an exceedingly modest cut, putting Pentagon funds back within the inflation-adjusted range of levels at the end of the Obama administration. If the Biden team wants a return to “normal,” this is a minimal ask. A ten percent cut could easily be structured to crack down on bureaucratic waste, or on war profiteering private contractors that deliver the lion’s share of their profits to CEOs, while scrapping unnecessary weapons systems and leaving untouched anything in the military budget that actually supports the troops, like employee pay and benefits. Finally ending the endless wars would save money—and moreover, the U.S. would stop killing so many people.

When accounting for how to reduce military budgets, we must be sober in not shifting with an ever-increasing topline target. For example, advocating for 10% of an ever increasing pie risks losses greater than gains. Climate activists recognize this, which is why CO2 emissions targets are tied to 1990 figures rather than later years. For a just reset in the longer term, it’s useful to identify hard numbers for even larger reinvestments that could free up even more resources, and contextualize them with past military spending.

In 2019, the National Priorities Project and Poor People’s Campaign proposed to safely shift $350 billion from the Pentagon budget, which would take it down to about $400 billion per year, matching US military spending during much of the 1970s and 1990s. That would still leave the U.S. with a bigger budget than the militaries of China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea combined. This would entail a fundamental reversal of the “War on Terror,” and a retreat from the posture of “Great Powers” conflict, with a decisive end to unwinnable wars in the Middle East, closing 60% of all overseas bases (leaving merely 300+), and more, opening space for a shift to real global diplomacy, cooperation, and solidarity.

In the wake of the storming of the U.S. Capitol by a mob of Trump supporters in the first week of this year, Biden and some Democrats proposed new laws against domestic terrorism, with increased funds to combat ideologically inspired violent extremists. This is a questionable prospect, judging from two decades of stark results of the post-9/11 creation and expansion of the Department of Homeland Security, with a long trail of violent abuses against the civil liberties of immigrants, racialized communities and political dissenters. In addition to 53% of the discretionary budget that goes to the military, another full 11% already goes to domestic militarized spending, including border enforcement, incarceration, and the war on drugs, which amounts to almost two-thirds of the budget allocated by Congress each year funding militarism. The last thing we need in response to right-wing polarization is an even more bloated security and surveillance apparatus—we need popular policies that actually meet people’s material needs and expand democracy.

Mass Organizing Against Militarism

Much more effective mass organizing is necessary to win such massive changes, and there are no shortcuts. The U.S. peace movement has played a crucial role in carrying the flame since the Vietnam War and nuclear disarmament movements through the 1980s. Amid the metastasis of the War on Terror, many peace groups have fallen into a mode of resisting wars reactively, following tactics fit for previous eras. The rise of dynamic intergenerational and multiracial leadership is an important step toward rebuilding the peace movement into a fighting force, and should be embraced.

Over the past decade, a generation of movement organizers has developed in the U.S. in successive waves of civil society politicization, through Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, immigrants rights, climate justice, and other struggles. A deep generational disillusionment with the military seems pervasive. Many young organizers draw natural intersectional connections from their main work to anti-militarism, without necessarily focusing most of their attention on it. New youth-led organizations like Dissenters are arising specifically to organize students to resist militarism and war. The rise in police and prison abolition activism is particularly fertile ground for making these connections. The past year’s flurry of organizing to “defund the police” has radically shifted political terrain—perhaps “defund the Pentagon” isn’t far behind.

In electoral politics, more outspoken progressives, particularly democratic socialist politicians like Cori Bush, Jamaal Bowman, and Ilhan Omar who are more willing to name and challenge the military-industrial complex, reflect the growing organization in the U.S. of young Black, Indigenous, and people of color who are descendants of immigrants from parts of the world that have directly experienced U.S. imperialism.

Activism against the military-industrial complex can only go so far without the power of organized labor. The Pentagon is effectively this country’s largest jobs program, with well-paying unionized manufacturing jobs distributed across many working class communities given few other options. In the 1990s, there was a national push for a “peace dividend” to shift resources away from the military after the Cold War, which had significant support from labor unions whose leaders pushed aggressively for military conversion planning and even Pentagon spending cuts. That kind of union support seems like a remote possibility now, with the labor movement historically weak and militarization so pervasive, but it’s crucial to rebuild.

Conclusion

During an unprecedented crisis, there are plenty of openings in the near term to make the political case for specific changes in U.S. budget priorities. The need to envision a coherent global order that makes real peace and justice possible, and build a solid power base within U.S. society to enact it in solidarity with people around the world, is more crucial than ever.

Biden talks a great deal about the need to restore the “soul of the nation.” He, and anyone who agrees, would do well to heed the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., in his famous “Beyond Vietnam” speech: “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” That was over 50 years ago. If the richest and most powerful nation in the world is to maintain any kind of integrity beyond the current political crises, it is well overdue for a revolution of values.

Ashik Siddique is research analyst for the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studied, working on analysis of the federal budget and military spending.