This article is part of our series “On the Precipice: A Progressive Agenda in the Biden Era.” Download a PDF of the full series here.

Throughout the Trump years, the specter of Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin, has haunted the American political discourse. In the aftermath of Russia’s well-documented interference campaign in the 2016 election—which took the form of hacked and selectively released emails, disinformation hyped on social media networks, and direct contacts between Russian intelligence and members of Trump’s inner circle—Democrats in particular have come to fear the Kremlin, and liberal-friendly media outlets like MSNBC have indulged Cold War nostalgia and offered platforms to paranoiacs and conspiracy theorists. Thus, with Democrat Joe Biden in the White House as of January 20, it’s reasonable to wonder whether the United States and Russia are entering a new era of superpower confrontation.

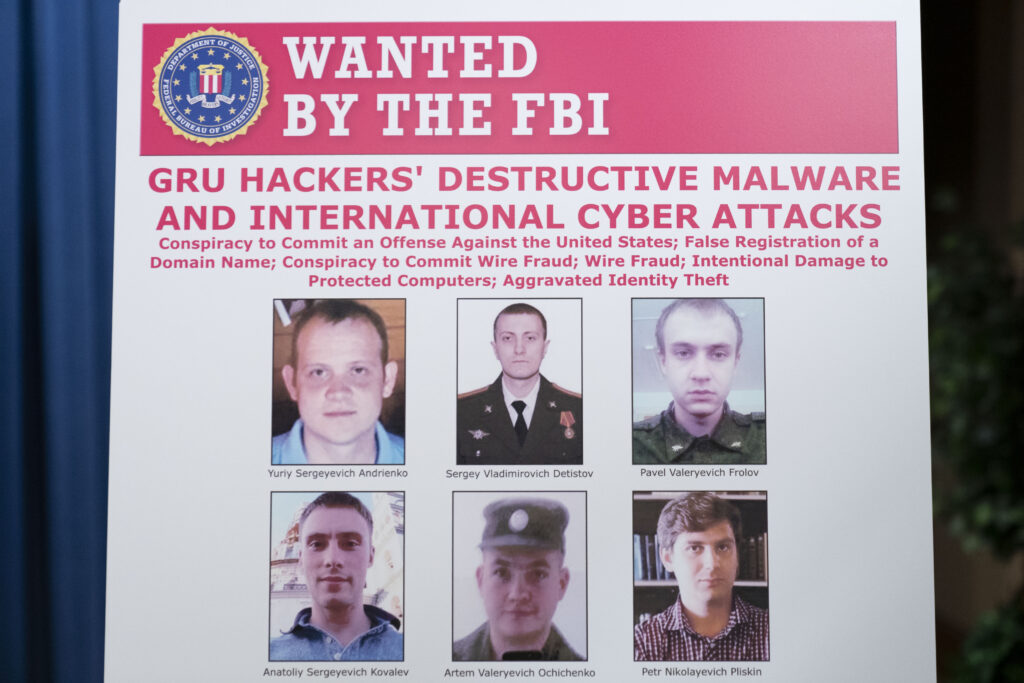

Russia and the U.S. are certainly not going to have warm relations anytime soon, and the Biden administration has every reason to treat Putin as a potential threat in light of 2016, as well Russia’s more recent cyberattacks on the U.S. government. But neither country can afford a new Cold War right now. To pursue one would spread chaos worldwide, impacting everything from energy prices in Germany, to political stability in Ukraine, to the safety of whole populations in Syria—all while squandering the resources the U.S. and Russia both urgently need to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, which has devastated both countries. Biden’s challenge will be to find ways to confront Russia that don’t rely on military buildups, and instead focus on the new battlefields Putin himself seems to prefer: the global financial system and the internet.

Biden and Russia have a long history. As a U.S. senator in the 1970s and 1980s, Biden traveled to Moscow to participate in arms control negotiations with the Soviet Union. As vice president in the 2010s, he was often the Obama administration’s point man in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet bloc, deployed to reassure NATO allies of Washington’s commitment to their security following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and instigation of the still-ongoing civil war in eastern Ukraine. Biden also led a campaign against corruption in Ukraine, even as his son Hunter Biden was infamously collecting a paycheck from Ukrainian oligarchs as part of their failed effort to win over his father. It was in response to this influence peddling that Donald Trump, in July 2019, would hold up military assistance to Ukraine in an attempt to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky into furnishing dirt on the Bidens. This scheme, in turn, led to Trump’s impeachment, as well as a persistent headache for Biden’s presidential campaign last year—one Biden’s inner circle believes is part of a wider Russian disinformation campaign against them.

Biden has made clear under his own byline that he intends to confront Russia as president. He has also relied for years on the advice of Tony Blinken, his nominee to run the State Department, who is generally seen as a representative figure of the Washington national security establishment, the so-called “Blob.” In a 2017 New York Times op-ed, Blinken proposed lifting restrictions on lethal military aid to Ukraine, including anti-tank missiles, which Barack Obama himself had refused to do as president despite much pressure from the Blob. The Trump administration followed Blinken’s advice, though not without protest from Trump himself. The lethal aid issue was emblematic of Trump’s incoherent policy toward Russia: Republican senators and career national security officials continued to push military confrontation with Moscow, even as the president routinely praised Putin, questioned NATO, and undermined longstanding US policy in the region.

With the selection of Blinken and the elevation of Victoria Nuland, one of the Obama administration’s leading Russia hawks, it seems certain that Biden will break with Trump’s personal deference to the Kremlin, and that he will not replicate the Obama administration’s initial pursuit of a “Reset” with Russia, a policy now widely seen as a failure. But early indications are that the Biden administration’s policy toward Russia will be sober-minded and will include restored cooperation on at least some issues. Jake Sullivan, the incoming national security advisor, said recently that Biden plans to renew the New Start missile treaty, an Obama legacy abandoned by Trump, which should reassure anyone who is concerned about a potential nuclear arms race. Sullivan also affirmed Biden’s commitment to resuming U.S. participation in the Iran nuclear deal, provided Iran meets certain conditions; since Russia is a key signatory of the deal and a frequent strategic partner of Iran, this creates at least some space for U.S.-Russian diplomacy to function over the next few years. Diplomatic cooperation will be crucial on other matters of international concern, from containing pandemics to combating climate change—which will inevitably require buy-in from major oil and gas producers like Russia.

It also seems unlikely that Ukraine will flare up as a battlefield under Biden. For all the intense debates that preceded it, the generous lethal aid package the Trump administration signed off on turned out to have little effect on the conflict in the Donbass, which has remained basically frozen throughout Trump’s term in spite of regular artillery exchanges and sporadic casualties. Russia neither escalated nor backed down in the face of U.S.-supplied armaments, and while Ukraine certainly wants victory, most of the country is untouched by violence and faces the more pressing issue of its endless struggle with corruption. If anything, the drama surrounding Hunter Biden has likely impressed upon both Joe Biden and Zelensky the imperative of avoiding any hint of improper ties between the two countries—which suggests that the status quo is likely to persist in the near term.

Likewise, the civil war in Syria, which on one level can be seen as a proxy war between the U.S. and Russia and which sharply divided Obama from many of his own national security advisers, will probably not feature as prominently on Biden’s watch. Syria’s president, the Russian-backed autocrat Bashar al-Assad, is generally understood to have prevailed against the various Sunni rebel groups covertly backed by the U.S. under Obama. Under Trump, the U.S. launched a missile strike on Assad’s airfields, bowing to pressure from the Blob that Obama had resisted—and nothing whatsoever changed. The carnage inflicted by Assad over a decade of war has been horrific, but the conflict is winding down on his terms, and the U.S. has no interest in re-escalating the war for the sake of geopolitical competition with Russia.

But while these conventional war zones will hopefully be contained, new theaters for U.S.-Russia competition could take their places. One is the arena of international capital. To the extent the original Cold War represented the triumph of U.S. capitalism over Soviet communism, the Russia it left in its wake is fully capitalist and integrated into the same global economy as the U.S. and Europe—as a leading oil and gas producer, as a consumer of German cars and French cosmetics and American iPhones, and as a point of origin for illicit capital flows into offshore bank accounts and Manhattan and London real estate. If Russia has a key vulnerability, it is the dependence of the oligarchic clique surrounding Putin on the willingness of the U.S. and its allies to launder their immense wealth.

A promising sign on this front is the new National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that passed earlier this month with enough bipartisan support to override Trump’s veto, which includes a provision effectively banning anonymous shell companies. The provision, of which Biden was an early supporter, simply requires the owners of shell companies to disclose their identities; in practice, this will greatly empower law enforcement agencies to police corruption, including the kind that Russia has been able to weaponize to influence U.S. politics. This is a measure that pre-2016 might have been shot down by the powerful real estate lobbies in cities like New York and Miami. A silver lining of Trump’s election is that the Blob now views international money laundering not just as unethical or criminal, but as a national security threat.

The Biden administration is likely to pursue additional measures to crack down on corruption. It could, for instance, expand enforcement of the Global Magnitsky Act, which grants the U.S. wide authority to apply targeted sanctions against corrupt officials in foreign countries. The original 2012 Magnitsky Act was passed in response to the jailing, beating and denial of medical care to its namesake, lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, in a Russian prison; repealing it appears to have been one of the core diplomatic goals Putin hoped to achieve by boosting Trump’s campaign in 2016. Instead, Congress passed new sanctions on Russia over Trump’s personal objections, but implementation has been minimal and haphazard. Under Biden, that could change, and Russia’s oligarch class could feel newly squeezed.

Biden plans on conducting an extensive review of Trump’s global sanctions regime. Many of Trump’s sanctions against countries like China and Venezuela were imposed unilaterally, which is generally ineffective. Biden has pledged to rebuild the State Department, which saw significant deterioration under Trump, and to recommit to diplomacy and to America’s traditional allies; such an effort could result in effective multilateral sanctions against the Russian elite, which are far more likely to sting. European allies have their own concerns about Russia’s corruption and human rights abuses, such as the recent attempted assassination by poisoning of opposition figure Alexei Navalny.

Cyberwarfare is also likely to expand under Biden, as his team is already contemplating attacks on Russian intelligence services and corporations in response to the recent barrage of hacks on U.S. government agencies. One indicator is Biden’s newly announced plan to establish a cybersecurity position on the National Security Council, thus elevating the profile of the issue, much as he is doing on climate. While a certain amount of retaliation is to be expected, this strategy carries risks of escalation; Russia has the potential to inflict serious damage on the U.S. through cyberwarfare, and the dynamic is less asymmetric than in the financial realm, where the U.S. enjoys major advantages. Ultimately, Biden would be wise to pursue multilateral diplomatic efforts, to include China and other major powers as well as Russia, in order to establish limits on cyberwarfare and prevent it from spiraling out of control globally. This will always be a diplomatic gray area, of course, with room for plausible deniability by all parties involved no matter what is formally agreed to, but all-out cyberwar is in no country’s interest, and has the potential to become a major domestic crisis when, for instance, banks and critical civilian infrastructure are targeted.

Regardless of how harsh a response Russia may deserve after the events of the past several years, Biden will have to balance that against both the risks of blowback in foreign affairs and the overriding priorities he faces at home in terms of ending the COVID-19 pandemic, repairing the severe economic damage it has caused, and attempting to undo Trump’s toxic legacies on climate, immigration, regulation, labor and the basic functioning of government. A “cold peace” with Putin may be the safest and most pragmatic policy.

The 2016 interference campaign itself, while it represented an unprecedented escalation, had its roots in the many instances over the previous quarter-century in which the U.S. acted in defiance of the Kremlin’s expressed wishes—intervening in Kosovo, pulling out of an ABM treaty, invading Iraq, expanding NATO eastward, overthrowing Moammar Qaddafi in Libya, encouraging “color revolutions” in Russia’s periphery and regime change in Syria, and directly criticizing Putin’s domestic conduct, as Hillary Clinton herself did in 2011 in response to election rigging. The merits of any of those specific policies can be debated, but what cannot be debated is that Russia has demonstrated the ability to inflict serious damage on the U.S. political system when its leaders feel they have been disrespected by ours. Biden would be wise to keep this in mind as he considers the most effective ways to hold Putin accountable.

David Klion is an editor at Jewish Currents and a contributor to The Nation, The New Republic, and other publications.