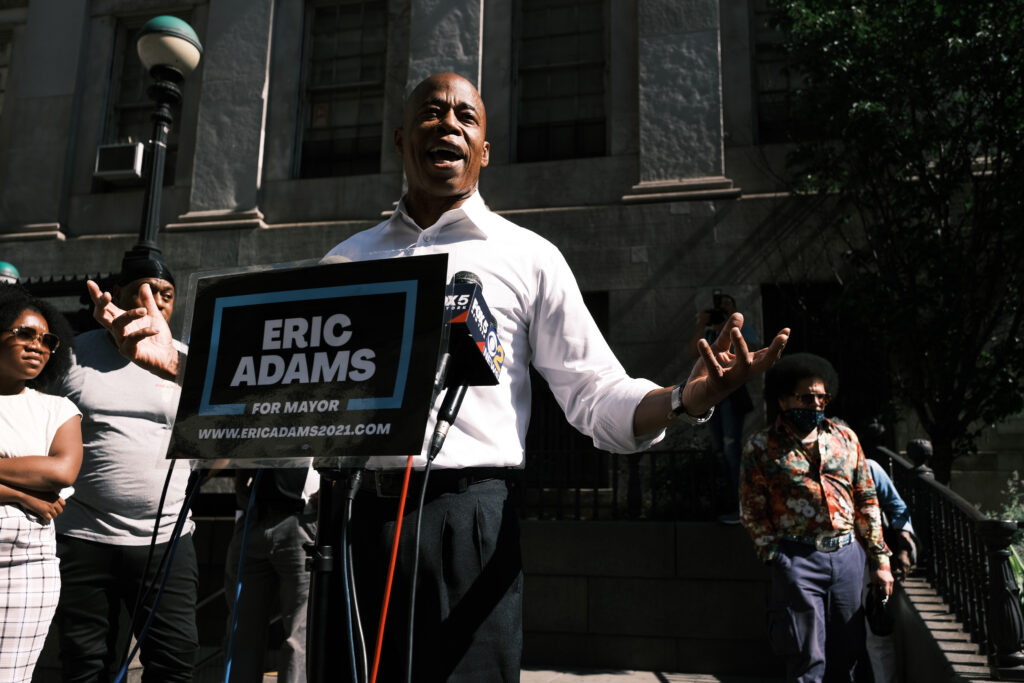

Eric Adams carried City Council District 9 in Harlem en route to his victory in the June 22 Democratic mayoral primary that all but guarantees he will be the next mayor of New York City.

Harlem voters also chose Kristin Richardson Jordan, a democratic socialist, to be their next City Council representative. Richardson Jordan wants to slash the police budget by 50% with an eye toward someday abolishing the police department altogether.

“It’s so bizarre,” Richardson Jordan told The Nation. “…They voted for someone who’s been talking about bolstering the police budget, more cops, and has a background in policing—and they voted for someone who’s been an out abolitionist.”

Adams, the most conservative of the eight leading Democrats in the race to replace outgoing, term-limited Mayor Bill de Blasio, also won District 40 in Flatbush. So too did Rita Joseph, a public school educator who called for cuts to the NYPD’s funding to be redirected to organizations working to end the school-to-prison pipeline. In Western Queens, Adams carried the public housing developments in District 22 as did another democratic socialist, Tiffany Cabán.

Why did such divergent results occur in the same election? The triumph of a stridently anti-Left candidate in the mayor’s race and numerous victories for the Left in down-ballot races reflects the different structural challenges candidates encounter in a high-profile, high-stakes campaign to lead a city of 8.8 million people as opposed to more localized contests. It also underscores that most voters are not strictly ideological in their choices but instead will gravitate toward candidates who they think understand their lives and will fight for them.

In the Mayor’s race, Adams proved to be an adroit politician who was able to both lean into his working class Black identity while also garnering ample financial support from ultra-wealthy New Yorkers who heard him repeatedly promise to govern the city to their liking.

Vowing to use his 22 years of experience as a police officer to lead a crack down on violent crime, Adams forged a victorious “rainbow coalition” of older, more conservative Black, Latinx and white voters in the outer boroughs of Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx, far from the cosmopolitan center of Manhattan.

“Social media does not pick a candidate, people on social security pick a candidate,” Adams told his supporters on election night.

Politics of Personality

Adams entered the race as a top-tier candidate after almost 30 years in the public eye. He drew heavily on his personal story of growing up poor and Black in an impoverished corner of Queens, of being beaten as a youth by the police and later joining the NYPD to serve his community. He first made a name for himself in the 1990s as a police officer who publicly challenged his superiors to end the department’s brazen racism.

Adams’ ideological leanings fluctuated during that decade as well. In 1994, he expressed support for Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Black nationalist Nation of Islam and a virulent anti-Semite. During Rudy Giuliani’s second term as mayor from 1997-2001, Adams became a registered Republican. He retired from the force in 2006 and successfully ran for State Senate as a Democrat and then Brooklyn Borough President, a largely ceremonial position which boosted his public profile and allowed him plenty of time to plan his mayoral run.

Endorsements from many of the city’s largest and most powerful unions bolstered Adams’ ability to sell himself as the candidate of outer borough Black and Latinx voters. Those unions included DC 37, which represents municipal workers, Transit Workers Union Local 100, the Hotel and Motel Trades Council and 32BJ which represents the security guards who commute into Manhattan to staff upscale commercial and residential buildings.

Adams also had another crucial base of support: The 1 Percent. He received generous support from big real estate, finance and billionaire backers of Charter schools—privately run schools that receive public funds. Unlike public schools, their workforce is not necessarily unionized. Less than six weeks before the primary, financial moguls poured millions into a pro-Adams Super PAC. Among the top donors was Kenneth Griffin, whose $240 million Manhattan penthouse is the single most expensive home in the city.

Mayor Bill de Blasio ran in 2013 as a champion of the vast majority of New Yorkers who didn’t see a place for themselves in the “luxury city” touted by his billionaire predecessor, Michael Bloomberg. De Blasio’s greatest achievement, remains instituting universal pre-K classes for all 4-year-olds, yet that occurred during his first year in office. He subsequently devoted himself to pursuing his quixotic presidential ambitions and rarely challenged the prerogatives of the city’s business elites. However, he made little effort to flatter them, which they deeply resented. Adams, on the other hand, promised to be a powerful salesman for their worldview and desired policies.

A New War on Crime

While the ruling class sought a full restoration in the halls of city government, Adams directed his campaign’s emotional punch at the public’s fear of crime, especially an increase in shootings and murders.

New York’s murder rate increased from 319 in 2019 to 462 in 2020, a jump of 45%. The 2021 murder rate, however, has dipped below the 2020 numbers as the roll out of vaccines allowed people to resume a more normal life after a year of high-stress lockdowns. 2020’s surge in killings fell well short of the modern-era record of 2,245 murders in 1990 and is equivalent to what the murder rate was in 2012 during Michael Bloomberg’s third term in office from 2010 to 2013 when he was widely hailed for his crime-fighting prowess.

The New York Post, owned by right-wing billionaire Rupert Murdoch, endorsed Adams and relentlessly hyped crime stories on one lurid front page cover after another to underscore the point that the city needed a tough, savvy cop at the helm. Local news coverage has declined precipitously over the past 20 years. The New York Times has discarded its Metro section and the circulation of The Post and its tabloid twin The Daily News have fallen dramatically as has their influence. They have both raged with little effect against incumbent Mayor Bill de Blasio since he first ran in 2013. But, at certain moments, the tabloids can still set the political tone and agenda for the City. This was one of those times.

To underscore its theme of a city out of control, The Post focused its wrath in particular on Washington Square Park, a popular Lower Manhattan destination for musicians and young, mostly people-of-color revelers from across the city who had endured more than a year of lockdowns and mass death. Older whites who own million-dollar homes overlooking the park complained about the young partygoers. The NYPD responded by establishing a 10 pm weekend curfew. On the night of June 5, 23 people were arrested at Washington Square Park when a police attempt to enforce the curfew sparked clashes between revelers and the cops.

So, why the outsized fear of crime when there is relatively little of it?

High-end real estate is to New York City what oil is to Saudi Arabia. Maximum profits lie in transforming poor and working-class communities into upscale, gentrifying neighborhoods that attract more affluent residents from outside the city. Any whiff of rising crime threatens the real estate industry’s project to turn as much of the city into an upper-middle-class suburb as possible. Tourism is another key local industry that shudders at the prospect of New York being perceived as unsafe.

At the same time, many older New Yorkers were traumatized by the day-to-day fear of being harmed they experienced during the high crime era of the 1970s and 80s. Any sign of regressing to the “bad old days” is greeted with dismay by these residents. Then as now, violent crime was highest in predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods that Adams overwhelmingly carried. Many of these same residents deeply resent the abusive policing their communities are subjected to. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean they support defunding the police department, much less abolishing it, as some activists urged during last year’s massive protests following the murder of George Floyd.

When Adams vowed that only he could rein in violent crime, he was speaking to both his elite and working class bases of support.

The Left Stumbles

The New York City Left entered the mayoral race with high hopes. Over the past three years, it had racked up a dazzling string of results:

- Defeating a 10-term incumbent Democrat and replacing him with the most famous congresswoman in America, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

- Defeating a 16-term incumbent congressperson known for his close ties to Israel and the arms industry and replacing him with leftist educator Jamaal Bowman.

- Defeating roughly a dozen machine-backed state legislators and moving the New York State government significantly to the left.

- Coming within 55 votes of electing Tiffany Cabán as district attorney of Queens, a borough of 2.6 million people. The DA’s office oversees criminal prosecutions. Cabán, a career public defender, spoke openly of her desire to see police and prisons eventually abolished at a future date.

The Left’s ability to perform so well in these races was aided by advantages that were not available to them in the mayor’s race. The first was the element of surprise. In 2021, the Democratic Party machine and its big money backers were not going to be caught napping again.

Second, the NYC Left’s previous insurgent victories had come in single district campaigns where they could flood targeted districts with volunteer canvassers and phone bankers who would personally make the case to voters for their candidate. Single district races in a large and expensive media market such as New York City were also immune to television advertising. Blanketing the whole city with television ads in a single district was an extravagant waste of resources for even the best-funded incumbent. In military terms, competitive single district races are the equivalent of hand-to-hand combat where the side with more highly motivated foot soldiers has the advantage, while a citywide race is more like an air war where the side that can drop the most bombs—in this case television ads—from 30,000 feet in the air has the upper hand.

In the race to choose a new leader for a city of 8.8 million people, the Left could not begin to personally contact millions of voters, while candidates flush with backing from the super rich could carpet bomb the airwaves with advertising.

The Left’s strongest potential mayoral candidate was Public Advocate Jumaane Williams who is popular with both a broad swath of Black voters and white progressives. When Williams opted to stay at his current post, the Left fractured over three flawed candidates —City Comptroller Scott Stringer, City Hall lawyer Maya Wiley and non-profit executive Dianne Morales—seeking to carry its banner with each garnering some support.

Stringer was the strongest candidate of the three. He had climbed the political ladder over 30 years from a seat in the state legislature to Manhattan Borough President to Comptroller. He was the only candidate in a crowded field who had previously won a citywide election and looked poised to build another winning coalition. He could draw on support from older voters who had backed him over the years. He had the second most union backing after Adams, and he had shrewdly moved to the left in recent years after decades as a conventional machine politician.

Stringer garnered early endorsements from Bowman and young leftwing state legislators including Jessica Ramos, Julia Salazar, Alessandra Biaggi and Yuh-Line Niou. As Comptroller, Stringer was responsible for auditing the City’s expenses. He used that experience to burnish his reputation for the kind of managerial competence that tends to excite upscale liberals who work in the professional managerial class.

Unfortunately for Stringer, he was also a dull and plodding campaigner whose promise to “manage the hell out of the city” failed to inspire a populace still reeling from the pandemic.

Wiley and Morales were both first-time candidates for public office who started with limited name recognition. For liberals who foreground identity-based concerns, both offered the prospect that New York’s 110th mayor would also be its first female mayor and a woman of color no less.

Wiley had served as legal counsel to Mayor Bill de Blasio and was best known as a legal commentator for MSNBC, a cable news channel popular with Democratic Party loyalists.

Morales had led large non-profit social service providers. She won a following among leftwing activists when she embraced calls to cut the NYPD’s annual budget by 50%—a position that both Stringer and Wiley refused to embrace. However, her leftist credentials would be dented by revelations of her extensive ties to the charter school industry over many years and her admission that she “probably” voted for New York State’s conservative Democratic governor Andrew Cuomo when he was challenged from the left in a 2018 primary.

All three progressive candidates languished in the polls for months. Stringer finally began to gain traction in the polls in mid-April, closing to within a point of Adams in one poll, while gaining endorsements from the influential Working Families Party and the United Federation of Teachers, the massive teachers union local. The New York Times’ endorsement—which has an outsized influence with its highly-educated New York City readers who vote in the Democratic primary—also seemed within reach. The Times had endorsed Stringer’s previous runs for Comptroller and his combination of managerial expertise and practical progressivism seemed likely to hit their sweet spot.

However, Stringer’s campaign imploded on April 28 when City Hall lobbyist Jean Kim accused Stringer of groping and forcibly kissing her when she volunteered on one of his campaign’s 20 years earlier. There were no direct witnesses to the misconduct Kim alleged, and she did not provide any corroborating evidence—email or text message threads or statements from family or friends she might have confided in at the time—that have become commonplace for assessing sexual misconduct allegations. Kim’s lawyer, Patricia Pastor, also worked as an attorney for a group of nonunion construction firms that had previously clashed with Stringer over his support for unionized workers at Hudson Yards, a real estate mega-project that had received billions of dollars in public subsidies.

Stringer insisted on his innocence and released information showing Kim seeking a job on his 2013 campaign for Comptroller. It made no difference. His high-profile millennial supporters and a number of progressive organizations rescinded their endorsements within days. Stringer’s campaign never recovered. Any pulse it still had was extinguished in early June when a second woman, Teresa Logan, also represented by Pastor, accused Stringer of sexually harassing her in 1992 while she was working at a bar he owned at the time. Stringer ultimately finished in a distant fifth place.

Morales’s campaign was next to stumble and then be devoured by the Left. In her case, it was campaign staffers who revolted against what they claimed were unfair labor practices and sought to organize a union less than four weeks from the primary. The image of Morales’s own staff denouncing their boss while protesting outside her Midtown Manhattan office destroyed any credibility she had as a candidate.

This primary marked the first time voters used a ranked-choice voting system citywide. Voters could choose their top five candidates in order of preference and then have those preferences redistributed upward as each lowest ranking contender was progressively eliminated in the vote count. Many progressive organizations, labor unions and elected officials took the opportunity to issue ranked endorsements, increasing their odds that if their top choice failed they could still maintain some goodwill with the eventual winner. One group that did not endorse at all in the mayor’s race was the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. It chose to focus on a handful of City Council races (see below) where its ability to marshal many hundreds of volunteers can have a decisive impact.

Following the collapse of Stringer and Morales, progressives belatedly tried to consolidate around Wiley with Ocasio-Cortez (who tends to get involved late in races) providing a key endorsement. Wiley’s poll numbers quickly jumped as younger and college-educated voters flocked to her. But it was too little late. The election night results saw Adams leading Wiley 31-22%. Former Sanitation Commissioner Kathryn Garcia, a centrist technocrat, whose campaign soared after receiving The Times endorsement, netted 19%.

On the race’s final weekend, Garcia campaigned with eventual fourth place finisher Andrew Yang, who encouraged his supporters to make Garcia their second choice. The three progressive candidates failed to form a similar alliance. When the final ranked choice votes were tabulated, Garcia surged past Wiley and came within less than one percentage point of defeating Adams, underscoring what a polarizing candidate he was.

For the Left, it was the final act in a season of missed opportunities and self-inflicted wounds. Because New York is a heavily Democratic city, Adams will face only token opposition in the November general election. Once his victory is confirmed, the New York City Left will see one of its most formidable enemies take charge of City Hall for at least the next four years. That four of the last five New York City mayors have leveraged the power of incumbency to win a second term offers little solace.

Down Ballot Victories

The Left fared much better in down-ballot races. Progressive City Councilmember Brad Lander succeeded Stringer as Comptroller. Running on a criminal justice reform platform, Alvin Bragg became the first African American elected to be Manhattan District Attorney. If he chooses to, he could be a powerful foil to Adams’ propensity to demagogue concerns about crime for political advantage.

Four open socialists — Kristin Richardson Jordan, Tiffany Cabán, Alexa Aviles and Charles Barron — were elected to the City Council, and roughly another dozen leftists won seats on the 51-member body, including some who come directly from social movement organizing. Sandy Nurse was a leader in organizing daily street protests during Occupy Wall Street and later founded a community center that serves the working class residents of the North Brooklyn neighborhood that voted her onto the City Council. Chi Osse led Black Lives Matter protests last year in Brooklyn. This year the 23-year-old queer Black community organizer defeated a machine-backed candidate by 14 points to win a Council seat. The new City Council will also be the most racially diverse ever and it will be majority female for the first time.

New York City has a strong mayoral system that concentrates power in the chief executive relative to the City Council. At the same time, the state government in Albany wields tremendous power over the City, controlling everything from its transit system to its tenant protection laws to its ability to levy new taxes to its ability to install traffic speeding cameras. Recently resigned Governor Andrew Cuomo rarely missed a chance to publicly humiliate de Blasio and reminding him who was the dominant partner in their relationship. Adams should fare better with incoming Gov. Kathy Hochul who has vowed to work in a collaborative manner with other political leaders and who will be seeking Adams’ support when she is up for election next year.

While it remains to be seen how much power a left bloc will be able to exercise within the City Council, Adams should expect left-leaning members to aggressively push a redistributive agenda that would expand a tattered social safety net. In doing so, they will challenge the new mayor to deliver meaningful change for the city’s multi-racial working class even if that offends his more well-heeled supporters.

John Tarleton is a co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Indypendent, a free progressive newspaper and website published in New York City since 2000.