Before March 2020, New York was already in the depths of a housing crisis. Decades of austerity governance and deregulation have weakened the city’s social safety net and transferred greater risk on to the shoulders of low-income communities of color, both through exclusion and through predatory inclusion. As a result, four out of 10 low-income New Yorkers are either homeless or paying more than half of their income toward rent. COVID-19 is now pushing hundreds of thousands of the city’s residents further into housing insecurity, and in search for answers to systemic housing problems that were already lurking just below the surface. At least 126,000 low- and moderate-income renter households had trouble paying their April rent. That number is likely to grow in May and June.

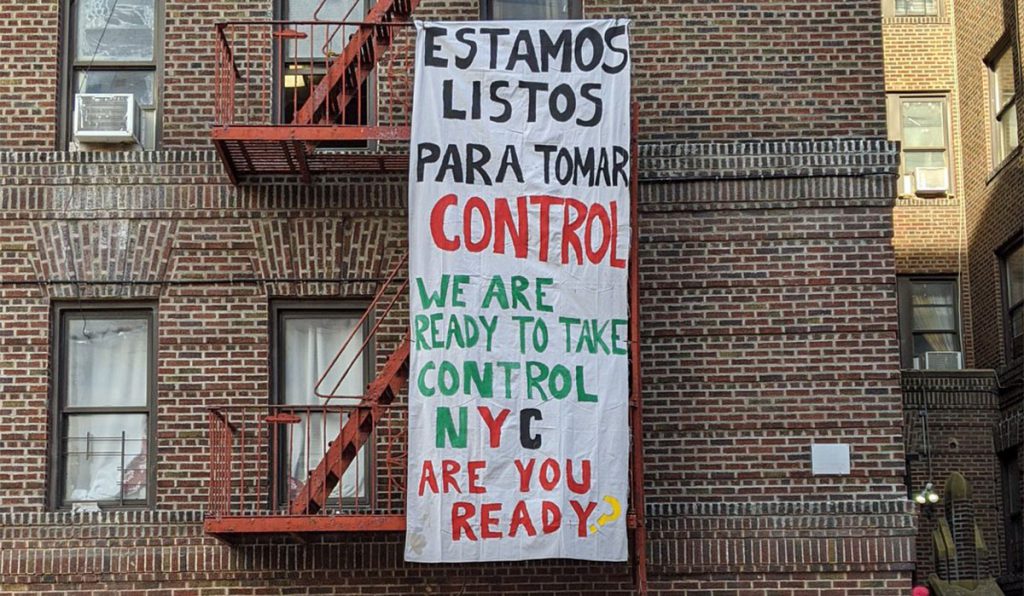

Today, New York is experiencing a surge of housing organizing activity, spurred by the social and economic impacts of the pandemic. In March, tenant groups pressured the State to adopt a comprehensive eviction moratorium, paired with a closure of housing courts. Building on this important first step, housing justice groups are now calling for immediate and safe accommodations for all New Yorkers living on the street or in congregate shelters, under the #HomelessCantStayHome hashtag. Organizers have also been advocating for universal rent cancellation (#CancelRent), to forestall a flood of evictions whenever New York’s eviction moratorium is lifted.

The foundation for #CancelRent and #HomelessCantStayHome is New York’s multifaceted housing justice field, which includes member-led groups like VOCAL-NY and Picture the Homeless. It also includes fluid and loosely-structured coalitions like the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition and the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance, made up of building-level tenants associations, city-wide social justice groups, as well as legal service and technical assistance non-profits. Over the past few years, these groups and coalitions have achieved a few significant campaign victories, which in turn has strengthened their organizing position.

In June 2019, the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance’s activism dramatically expanded New York State’s rent regulation system, which covers approximately one million apartments statewide (and, about half of the rental stock in New York City). New York’s modern form of rent regulation has been on the books since 1974, but was weakened by politicians in alignment with powerful real estate interests and motivated by anti-regulatory ideology, ultimately leading to the deregulation of 291,000 stabilized units.

Organizing for stronger rent laws in New York occurred in parallel to the struggle for Berlin’s rent cap, officially implemented in February 2020. Tenants in both cities have struggled with increased financialization of their multi-family housing stock. And, landlords were able to exploit gaps in both rent control systems in similar ways. For example, like in Berlin, New York landlords were able to use capital repairs to facilitate permanent rent hikes. Ultimately, Berlin’s five year rent cap is a stronger, and more universal, mechanism. However, New York’s new rent laws no longer allow landlords to remove apartments from rent regulation, bypass the annual rent adjustment process, and automatically increase rents upon vacancy, thus incentivizing evictions of long-term tenants.

New York’s strengthened rent laws came at the heels of other victories for housing justice organizers, including the implementation of a municipal right to counsel law in 2018, which will give all low-income tenants facing an eviction the right to an attorney. And, not all successes were legislative. A broad coalition of anti-gentrification, labor, and immigrants’ rights groups scuttled Amazon’s plans to build a headquarters in Long Island City, Queens in early 2019. While this coalition grew out of place-specific networks and hyper-local projects, its oppositional ethos was broadly similar to the resistance to Google’s campus in Kreuzberg, Berlin: concern over gentrification, skepticism about promised economic benefits for the neighborhood, and opposition to the corporation’s business and labor practices.

These successes were a result of a confluence of two factors: an opportune political moment, resulting from electoral groundwork that elevated state and national progressive candidates in 2018; and, longer-term organizing in the face of deregulation and austerity politics, which ultimately cracked the growth machine consensus in New York. This foundational work was done by hundreds of people, often behind the scenes. They include Carmen Vega-Rivera, a long-term anti-displacement organizer from the Bronx, who passed away in December 2019, and my colleague Tom Waters, a housing researcher and advocate for stronger rent regulation, who passed away in April 2020.

Housing justice has always been central to the core of movement building in New York, whether it was revolutionary organizing for Black and Puerto Rican self-determination in the 1960s and 70s–when the New York chapters of the Young Lords and the Black Panther Party along with the Metropolitan Council on Housing called for all rental housing to be put “into public ownership under tenant control”–or radical labor visions at the turn of the century. By the same token, New York was, and continues, to be a particularly difficult place for housing organizing. Real estate capital is deeply influential in the local political and planning processes. Deep race and class-based inequities are amplified by how expensive the city is.

Given this dynamic, and in the wake of the pandemic, there is a danger of a combination of government austerity and disaster capitalism to undercut the gains made by housing justice organizers over the past few years. The cuts to the city’s public social safety net, increased pressure on nonprofit service providers, and a rollback of other progressive victories–like bail–are apparent in the New York State and New York City’s budgets for the upcoming year. The usual forms of mass collective action–like rallies and pickets–have become difficult or impossible during the era of social distancing.

Still, the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance’s email list went from 6K to 100K people in less than a month, and the idea of a mass rent strike has re-entered the city’s parlance. There is an inherent hopefulness in the surge of basic acts of solidarity and compassion, mutual aid projects, creative plans for socially distanced mass actions, and visions for a just recovery that includes a better, more equitable housing system.

Oksana Mironova is a writer and researcher who was born in the former Soviet Union and grew up in Brooklyn, NY. She writes about cities, urban planning, housing, and public space. You can follow her on twitter @OksanaMironov or read more of her writing at oksana.nyc.