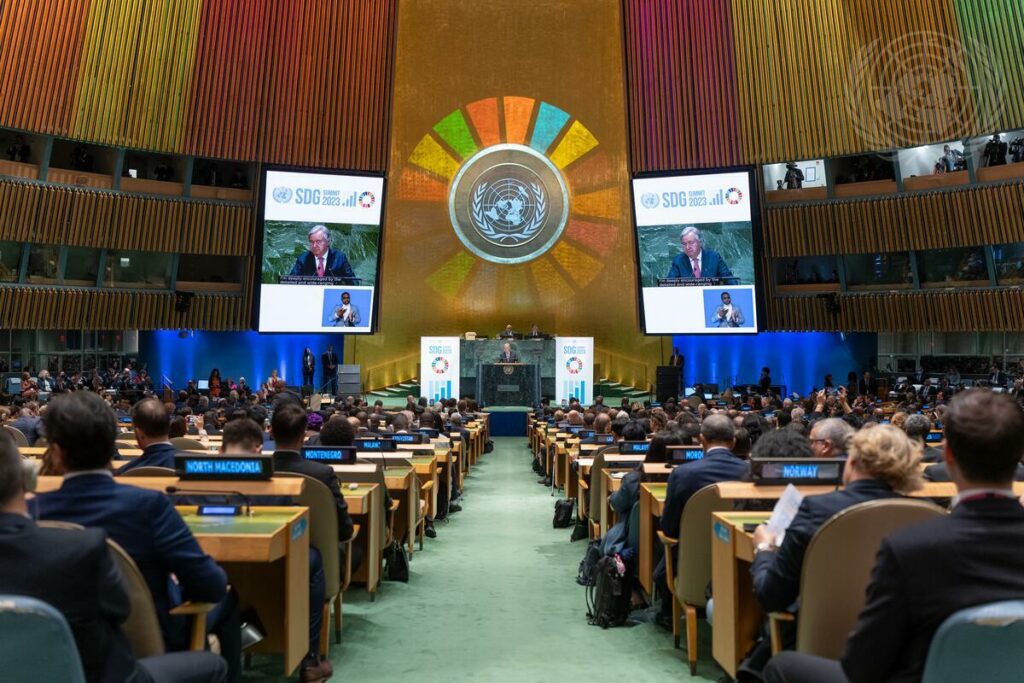

All roads led to New York in September with the convening of the 78th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. There were other high-level events held alongside the UNGA to make the most of this coming together of more than 290 of the world’s leaders, therefore forming a “UN Summits Week.” This year, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Summit and the Climate Ambition Summit (CAS) were just two of many high-level events organized by the UN. More than 10,000 delegates and almost 3,000 media representatives took part in this annual diplomatic shindig.

It is important to understand what these summits delivered and gauge whether or not these summits and their outcomes reflect the gravity and urgency of the crises of majority of the world’s people, and the planet writ large, or if this UN pomp and pageantry was merely an exercise of grasping at straws.

SDG Summit

The SDG Summit held on September 18-19 was the centerpiece of the UN Summits Week, as this year marked the midway point in a 15-year commitment to 17 goals, 169 targets and 247 indicators to bolster human development. Against a backdrop of surging socio-economic inequalities, an intensifying cost of living crisis and the escalating planetary crisis of climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss, there was nothing to cheer about at this “halftime summit.” Since the adoption of the SDGs in 2015, the results

have been lackluster: 15 percent of the Goals are on track to succeed, 48 percent are moderately or severely off track, and 37 percent are stuck or getting worse.

Addressing the world leaders in attendance (Afghanistan, Myanmar, Madagascar and Niger were missing), UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said “determination is in the DNA of the United Nations.” He reminded member states of the UN Charter that affirms human rights, dignity, equality, social progress and international solidarity. The SDG Summit sought to muster renewed commitment towards the Goals and prove that Agenda 2030 remains the roadmap for sustainable development. However, it was mostly generic statements and a reiteration of business-as-usual approaches from the 194 leaders that took the floor during the Summit, which were not exactly overflowing with ambition or new commitments, nor did they inspire hope.

The SDG Summit resulted in the adoption of a pre-negotiated Political Declaration that stated the obvious: the achievement of the SDGs is in peril, and that there is a need for “bold, ambitious, accelerated, just and transformative actions.” The Declaration was a paper tiger. It appears seemingly strong and aspirational, but lacks actionable items that would go the way of transforming the “outdated, dysfunctional and unfair” international financial architecture, and address the global debt crisis that has weighed down 60 percent of low-income countries and at least 25 percent of middle-income countries. The Declaration was the consequence of a consensus-building process among governments, with developed countries gaining the upper hand on contentious issues around their obligations particularly on aid and debt.

Although the SDG Summit affirmed the Secretary General’s call for reforms, it was silent on developing countries’ demand to democratize global economic governance, including the quota system and voting rights of member countries in international financial institutions. It also sent conflicting signals with the appeal for multilateral development banks to increase lending by USD 500 billion yearly to “rescue the SDGs.” In a bid to accelerate the achievement of the SDGs, the UN also launched 12 high impact initiatives that address issues such as digitalization, food systems and energy transformation, jobs and social protection, financing, trade and education.

Climate Ambition Summit

There have been two previous UN climate summits convened since the adoption of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. The first was in 2019 to encourage governments towards swift implementation, and the second in 2020 to get broad support from governments and non-governmental leaders.

The Climate Ambition Summit (CAS) convened on September 20, days after a massive march in the streets of New York and in 65 countries globally, where more than 600,000 people demanded an end to fossil fuels. The CAS called on leaders to:

- have ambition and enhance their contributions to national climate actions;

- have more credibility and commit to real emission cuts without using offsets; and

- to cooperate with all actors, including civil society and the private sectorto deliver actual implementation on the ground.

Countries gained an invite to the Summit if they met a certain threshold for climate action, and those that could prove ambition earned a speaking slot. The CAS featured speeches from leaders who the UNSG believes are accelerating global climate action, including Brazil, Canada, the European Union, Pakistan, South Africa and Tuvalu. Missing from the list of speakers were most of the world’s biggest historical and current carbon emitters like the United States, China, the United Kingdom, France and the United Arab Emirates – the host of the UN Climate Conference in December.

UN Secretary General Guterres warned that the “gates of hell” are at hand and called out those who are not doing nearly enough. There were strong statements against the fossil fuel industry at the Climate Summit. California Governor Gavin Newsom said “the climate crisis is a fossil fuel crisis.” Chilean President Gabriel Boric called out the deceit and corruption of the fossil fuel industry. Tuvalu’s prime minister, Kausea Natano, advocated for a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty. Mia Mottley, Barbados’ prime minister, said that “with the fossil fuel industry making profits of USD 2.5 trillion, they have more than enough profit left to ‘fill their belly’ and should contribute to the Loss and Damage Fund.”

International financial institutions also featured prominently at the CAS, but it was clear that their take on financing climate action—including loss and damage—are still within the realm of providing loans, co-financing and private sector responses (insurance).

The most notable takeaways from this “no-nonsense summit” were Germany’s early pledge to top up the Green Climate Fund, Denmark shifting its net zero goal forward to 2045, and Brazil’s commitment to undo the previous administration’s backsliding on its climate target. Colombia and Panama joined a coalition of governments committed to stop building coal plants and phase out the ones they have.

High-level Dialogue on Financing for Development

The High-level Dialogue on Financing for Development (FfD) was also convened on September 20 in the hopes of fostering a renewed commitment to tackling challenges in the global economy and encouraging public and private financing for the sustainable development agenda. The UN Secretary General likened financing to fuel that drives progress on the Agenda 2030 and the Paris Climate Agreement, but that this fuel is running out as progress on some fundamental development priorities has even reversed. With a global cost-of-living crisis affecting billions of people, the war in Ukraine, the lasting impact of the COVID pandemic and climate crisis on developing economies, Guterres said international finance institutions (IFI) were “deeply skewed” in favor of developed countries. It has enabled donors to abandon their development and climate finance commitments, facilitated corporations’ plunder of the global South’s resources, all of which has left an increasing debt burden on developing countries. He spoke of the systemic problems of financing requiring systemic solutions.

The UN chief called for a new “Bretton Woods moment” and appealed to all to deliver on his USD 500 billion a year SDG Rescue Package, with a prominent role given to IFIs and multilateral development banks. However, developing countries have a more urgent agenda that spoke to how, particularly because of debt and illicit financial flows, they are unable to finance much-needed social protection, infrastructure and other programs to achieve sustainable development and climate action. The Africa Group criticized the international financial architecture for its failure to live up to the expectations and needs of developing countries. They called on the UN to establish a binding tax convention to address the crippling issue of massive resource drain from the global South.

Although the High-level Dialogue on FfD affirmed the dissatisfaction of developing countries on the systemic shortcomings of the international financial architecture, it also showed their hope in the UN to make good on its responsibilities in bringing forth much-needed transformative pathways to a new global economy. With the UN’s “one country, one vote system”, developing countries have a much greater say on democratizing global economic governance. This is unlike the IMF or World Bank, where voting power rests on the contributions shareholders have made. This has certainly raised expectations that the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in 2025 will be a crucial moment for tackling systemic issues such as aid, international trade, taxes, technology, and others head-on.

Sound policies, not just soundbites, needed

There were other high-level meetings organized throughout the week, including those that discussed universal health coverage, pandemic prevention and response, the fight against tuberculosis, financing for loss and damage due to impacts of climate change, and a preparatory meeting for next year’s Summit of the Future. These may give one the impression that the UN leadership is demonstrating strong progressive leadership to reinvigorate multilateralism and make it once more relevant in addressing global challenges.

A plethora of sound bites certainly makes for good copy, and diplomats are quite adept at dishing these out. A deeper dive into the process, substance and outcomes of these meetings, however, shows that these continue to be but a talk shop of states and multilateral institutions that offer very little in terms of concrete transformative actions and genuine accountability.

There was hardly any attention given to discussing and breaking down systemic barriers that continue to weigh down developing countries’ ability to recover from the pandemic, provide crucial social services to its people, and deal with the increasing onslaught of climate impacts. Actors who have historically contributed, and continue to exacerbate many of today’s global problems are heralded as solutions, benefitting from increasingly privileged partnerships with governments and multilateral agencies. Worse, communities and population groups on the intersections of the multiple crises continue to be excluded and silenced.

UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed said of the SDGs, “there is water in the glass; it is not full but it isn’t empty.” Could this be the same about the UN Summits Week then?