This article is part of our series “On the Precipice: A Progressive Agenda in the Biden Era.” Download a PDF of the full series here.

The past four years of the Trump administration’s multi-pronged attempts to hollow out public education—through changes in the tax code, the expansion of markets through choice policies and voucher-schemes, attacks on labor, rescinding civil rights, and codifying curriculum and teaching—demonstrate the significance of education as one of the last remaining public goods in the United States, and as a site of some of the fiercest battles of liberation movements in the U.S. and elsewhere.

What should the Biden administration do when it comes to education? The question provokes us to return to Audre Lorde’s insight, that there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we don’t lead single-issue lives. Indeed, as education studies scholar Jean Anyon wrote, “[e]ducation is an institution whose basic problems are caused by, and whose basic problems reveal, the other crises in cities: poverty, joblessness and low-wages, and racial and class segregation…a focus on urban education can expose the combined effects of public policies, and highlight not only poor schools but the entire nexus of constraints on urban families.” That is, the escalated and daily war on Black, Brown, immigrant, and poor communities through countless policies and practices (ranging from ICE raids to cuts to food stamps) is also an intensified and systemic attack on the public infrastructures (schools) charged with reproducing life through education and daily acts of care.

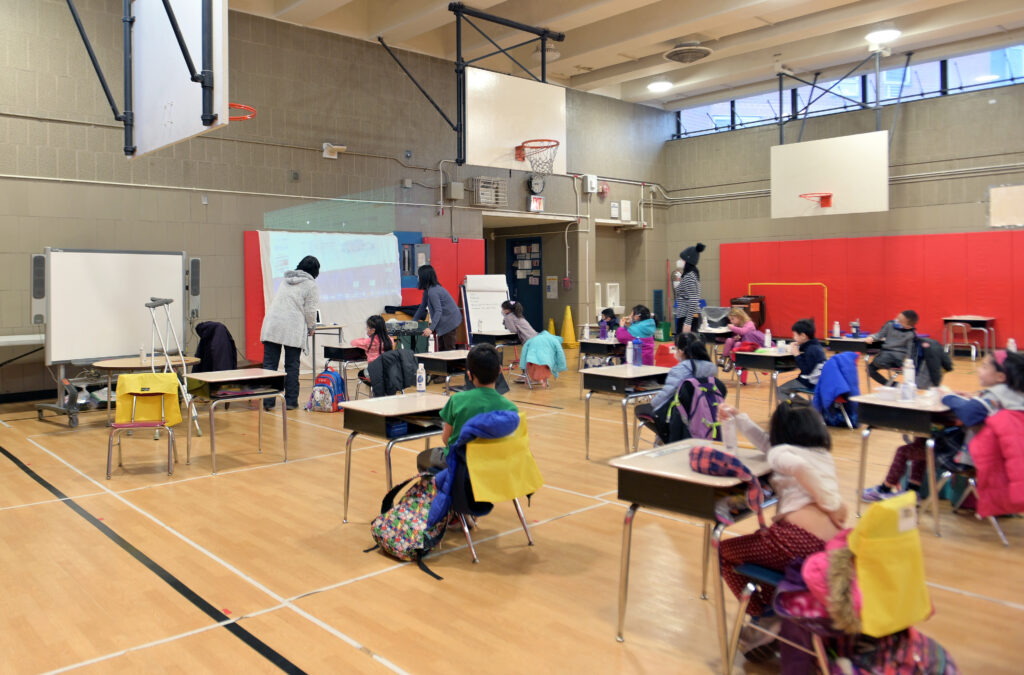

While public schools have historically worked counter to this charge of promoting care, well-being, and development and instead, have often functioned as sites of racialized dispossession, they also present a terrain of struggle over what our social relations might be. The global pandemic has brought this reality of interconnectedness and vulnerability and the race—and class—based fault lines of deep structural inequities into sharp focus. The crises of the past year have also raised questions related to the role of the state and the meaning—and structure—of the public, highlighting the need to move beyond individual solutions to collective problems.

Yet this basic tenet has become harder to imagine in the accelerated version of racial capitalism in which we live, where Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s call to “invest in individual students not school buildings” echoes, of course, Margaret Thatcher’s famous declaration that “there’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.” This is the logic that guides, for example, the initiative to “reimagine education” that New York State is partnering with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation on, and that which has also guided education reform for decades.

As we enter the Biden administration, many policy analysts are calling on the Biden administration to look back toward many of the Obama-era education reforms as a roadmap. But going back to a “normal” neoliberalism is the opposite of what we need. It was during the Obama administration that Race to the Top, essentially a structural adjustment program for public education in the United States, along with the reformist reform of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), were passed. ESSA largely affirmed and re-packaged Bush administration’s draconian No Child Left Behind Act, which pushed forward an aggressive neoliberal agenda in education that included the establishment of mandatory high-stakes tests for grades 3-8 as well as school choice policies. Among other measures, ESSA maintains standardized high-stakes testing, teacher merit pay, and mandatory military recruitment at high schools that receive federal funding. It was also the Obama administration’s education policies, including the promotion of austerity budgets as the “new normal,” that laid the groundwork for the conditions that propelled teachers across the country to organize insurgent wildcat strikes over the past several years; and, of course, it was during the Obama administration that Black Lives Matter was founded. In other words, the normal signified by the Obama administration was killing us.

So what should the Biden administration do about education? This is a hard question to imagine asking of a president-elect who is known for having staunchly opposed school desegregation efforts, sponsored of the 1994 Crime Bill, and who, in recent remarks on #defundthepolice, noted that he was opposed to taking money away from police budgets and instead, favored getting more money to ensure greater “effectiveness” in policing. While Biden claims to be a “friend of education,” and especially teachers’ unions, he supported the No Child Left Behind Act and also backed a 2005 bill that “made it nearly impossible for students in financial distress to discharge their student loans.” It is also a hard question to ask of the incoming Vice President-elect Kamala Harris who—despite her invocation of her parents’ commitment to Black freedom struggles—fought for measures that are fundamentally opposed to Black freedom, among them, one that “raised the financial penalty and made it a criminal misdemeanor for parents, up to a year in jail, when their children missed at least 10 percent of school time.”

While it is hard to imagine what to ask, or expect, of the Biden administration, the crises of the past year have made clear the stakes of the question. The global pandemic has demonstrated the essential role of schools as public infrastructures that are a backbone of the local, state, and national economies and integral to the functioning of society at large. It has also taught us that anything—and everything—is possible, and that we must be led by the radical imagination of the grassroots.

The long standing organizing undertaken by parents, teachers, and students have made changes that we were told were not practical, or possible. When it comes to high-stakes standardized testing, for example, communities drew upon their lived experience, as well as volumes of research that demonstrate the historical roots of such exams in racial science, making clear the multidimensional harms of testing policies. It was this organizing that made it possible that, in a time of “emergency,” federal and state officials determined that testing could be cancelled for the duration of the pandemic. Other things that we were told were not “realistic” range in scope and scale from the provision of school nurses, to eviction moratoratoriums that ensured increasing numbers of students do not become houseless. We need to continue these measures beyond the pandemic, and expand these wins to include the immediate and full cancellation of student debt as called for by the Debt Collective. This debt has been accumulated as the result of higher education trying to save itself through the creation of new (student) markets, intensified corporatization, and predatory lending.

Indeed, we have learned much in the past months about political will, as well as the need to be bold in imagining what we determine to be “winnable.” As historian Robin D.G. Kelley reminds us, creativity, experimentation, and freedom dreams are integral to progressive social movements. As he writes, “We must remember that the conditions and the very existence of social movements enable participants to imagine something different, to realize that things need not always be this way.” That is, the things we have today would not have been possible if people had not imagined, made, or fought for them first. The Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast for Children Program, established in 1966, being one of the most famous examples, which provided model for the national school breakfast and lunch program six years later. Rather than more of the same, in asking what the Biden administration should do about education, it is to the concrete demands produced by the radical imaginations of the grassroots in daily and multi-scalar struggles that we must look.

The recently passed COVID-19 Economic Relief Bill allocated $82 billion broadly to education (Education Stabilization Fund). Of these funds, $54.3 billion are directed to K-12 public schools, 90% of which needs to go to public schools with allotments “based on their proportional share of ESEA Title I-A funds.” The distribution of the remaining 10% of funds are left to the discretion of states. Yet, these combined federal relief funds are a far cry from what is needed, as “[a]dvocates for public education estimate that schools have lost close to $200 billion so far.” The impact of these piece-meal relief funds will be largely determined in struggles over budgets this next year, which will determine if the funds simply fill in the gaps of austerity budgets or if they provide some much needed resources. Moreover, the Education Stabilization Fund (ESF) does cover costs associated with the E-Rate program, which aids schools in purchasing computers and internet access. In line with the DeVosian logic of investing in students, not systems or school buildings, the ESF does “include funds meant to help low-income families access the internet.”

It’s clear that budgets will continue to be a key battleground site, and as we approach this next year of budget struggles, we can learn from the research, organizing, and demands put forward by the Los Angeles Teachers Union (LATU). They have linked calls to defund the police to an increase in state funding for schools, the expansion of schools (and jobs), a moratorium on charter schools, and an end to housing security. Operationalizing the abolitionist driven invest-divest framework and drawing on a key policy platform of the Movement for Black Lives, the LATU and the student, teacher, and parent-led #StudentsDeserve envision and demand “real support for Black communities, communities of color, and poor and working class communities of color.” As #StudentsDeserve explains, This means schools with smaller class sizes and more arts, electives, college counselors, therapists, librarians, custodians, and healthcare services….Investing in public schools is also part of challenging policing, privatization, charter school expansion, and reconstitutions or school closures and conversions. When our communities have well-funded and high quality public schools, we don’t need to turn to charter schools or rely on policing.” LATU and #StudentsDeserve remind us, schools are institutions of the state. Instead of austerity or state withdrawal, we need a redistribution of funding. We need to #defundthepolice and a new deal for public education.

This next year, as our cities emerge from the pandemic, will be a year of intensified local—yet networked—struggles. Recently, the New York City MTA threatened to slash over nine thousand jobs and cut service dramatically. At the same time, as school workers across the nation are fighting to keep schools closed amidst the surge, debates have also ensued as to how school district budgets—and jobs—will be impacted. Currently, there are over six million public school workers in the United States. As questions loom regarding what public school enrollment will look like, a recent study from the Pew Charitable Trusts notes that “U.S. Department of Labor estimates show that state and local education employment was down 8.8% in October from the previous year, representing the lowest national jobs total at that point in the school year since 2000…The majority of the mostly temporary education job cuts have hit local public schools, driving employment in the sector down in nearly every state from September 2019 to September 2020.” Further, recent reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in December 2019, 140,000 net jobs were lost nationally. That Black and Latinx women account for the entirety of the net jobs lost reminds us once again—in no uncertain terms—that the violence of austerity works through race and gender.

As we face intensified precarity, we can learn much from looking to movements of the Global South and their long-standing struggles against neoliberal reforms that have only guaranteed the violence of political and economic insecurity. The historic farmers and agricultural workers’ strike in India, for example, is an articulation of the radical imagination to which Kelley refers. We can also look to the organizing waged by poor and working class communities of color who have long-confronted precarity in the Global North, many of which have been emboldened by a concept that Henri Lefebvre termed, the right to the city. As geographer Kafui A. Attoah explains, the right to the city “signifies the right to inhabit the city, the right to produce urban life on new terms (unfettered by the demands of exchange value), and the right of inhabitants to remain unalienated from urban life.” Or, as one member of Operation Move-In, a squatting movement on New York City’s Upper West Side in the 1970s, led by El Comité-MINP (Movimiento de Izquierda Nacional Puertorriqueño/Puerto Rican National Left Movement), put it, “[w]e are the people who build this city. We work here. We work in factories, hospitals, supermarkets, subways, banks….so we are the city.” It was also El Comité that fought, for over a decade during the same time period as Operation Move-In (and building on the legacy of the Movement for Community Control of Schools), to establish one of the first dual language programs in New York City (also on the Upper West Side).

To be sure, the fight for schools is a dialectical fight, against the race and class based dispossession of organized abandonment, and for the place-making project of collective futures. Looking back to the #FightforDyett’s 34 day hunger strike embarked on in 2015 by Black parents, grandparents, teachers, and community members in Chicago’s historic Bronzeville neighborhood, we see that embedded in contestations over schools is a question of in whose image our cities will be remade. To be sure, the Coalition to Revitalize Dyett was about re-claiming, defending, and transforming a school and the place of Bronzeville. As education studies scholar Eve L. Ewing points out, the coalition’s proposed plan for the school “was based on community outreach to local parents over the course of 18 months and was intended to create a sense of stability and solidarity in a part of the city rocked by years of school closures.” Ewing reminds us that “[a] fight for a school is never just about a school.” Indeed, it is a fight for people in a place, and the joined futures of the two.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore notes that “Policy is to politics what method is to research. It’s the script for enlivening some future possibility, an experiment.” It not by chance that liberation movements from the Zapatistas to the Cuban revolution to the long Black Freedom struggle in the United States—and beyond—have identified education as a key means, method, and site of struggle in the gargantuan experiments of liberation. In the United States, as W.E.B. DuBois teaches us in the freedom making experiment that was Black Reconstruction in American 1860-1880, the first truly universal public schools were set up by free Black communities in the reconstruction period. As we look to the Biden administration, let us invoke this legacy of insurgent experimentation and radical imagination, and be guided by the expertise and grounded praxis of grassroots movements.

Ujju Aggarwal is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Experiential Learning in the Schools of Public Engagement and an affiliate faculty member in Global Studies and the Department of Anthropology. Her research examines questions related to public infrastructures, urban space, racial capitalism, rights, gender and the state.