Organized labor has been on the move. Will it be able to change class relations?

When 2022 began, Shawn Fain was one of two candidates in a runoff election for the international presidency of the United Auto Workers (UAW), the largest manufacturing union in the United States, with 400,000 active members and 600,000 retirees. The results of the prior election, between the reformer–a staffer and former local leader from Kokomo, Indiana–and reigning president Ray Curry, had been too close to call.

The election was the first in UAW history in which the membership would directly elect their highest leaders. The change followed a vast corruption scandal that landed twelve UAW officials, including two former presidents, in prison. A federal monitor appointed to oversee reform in the wake of the scandal recommended the union hold a referendum on changing the system of delegate elections that the Administration Caucus, the only caucus in the union’s seventy-year history, had used to maintain power. In 2021, the referendum saw 63 percent of ballots favoring direct elections.

Fain ran for the international presidency as part of the UAW Members United slate. That slate was backed by Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD), the first-ever reform caucus in the UAW, of which Fain is a member.

The union has been much diminished since its heyday in the twentieth century when it played an outsized role in the country: the proclamations and maneuvering of Walter Reuther, its most famous leader, were once front-page news, and its contracts set the standard for blue-collar work across industries. Its numbers peaked in 1979, with 1.5 million members. The following decades saw not only a bleeding of members, but concessionary contracts, overseen by leaders who far too often saw the union as their personal piggy bank, content to oversee its decline and raid its coffers. The formation of UAWD, and the push for direct elections, was rank-and-file members’ attempt to change all of that and take back their union.

In the 2022 election, the reform slate contested seven seats on the international’s executive board under the slogan “No Corruption. No Concessions. No Tiers.” In six, they were outright victorious. But as the new year began, they awaited the rerun between Fain and President Curry.

When the votes were tallied in early March of this year, the race was still a nailbiter. Of the more than 140,000 votes cast, only a few hundred separated the candidates, less than the number of challenged ballots. As the UAW prepared for its special bargaining convention in Detroit, where it would hammer out priorities for upcoming negotiations with the Big Three automakers–Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis– the slow process of sorting through the 1,608 challenged ballots continued.

But just before the convention kicked off, the results came in: Fain had won the race by a margin of roughly five hundred votes. On Sunday, March 26, the fifty-four-year-old electrician was sworn in as international president of the UAW. The next day, he was leading the convention.

“I was running the convention with no planning, no agenda, and no staff in place,” Fain told me. “You saw that house, how it was that day: it was very divided, it was very cold.”

Upturn for Labor

Not for long. Following the convention, the UAW began preparing for the negotiations, building contract campaigns in Big Three locals across the country and trying to undo the apathy that the prior leaders’ duplicity had created among the membership. In the meantime, workers elsewhere across the United States, too, were in motion.

There were strikes in the entertainment industry: 11,500 film and television writers struck in May, and would stay out for 148 days. Not long after the writers walked out, 160,000 actors and performers joined them, and would remain on strike for 118 days. There was a near-strike by the 340,000 Teamsters who work for the United Parcel Service (UPS), the largest private-sector contract in the country. There were strikes at Rust Belt manufacturing facilities and West Coast health-care giants, on college campuses and in the media, at both local newspapers and digital outlets alike.

All told, more than 500,000 workers went on strike in 2023 in the United States, more than double the 224,000 that struck last year, which itself was double 2021’s numbers, according to Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker.

New organizing, too, took hold in the unlikeliest of places. At Amazon, despite extraordinarily high turnover and unflinching executive opposition to unionism, workers continued early-stage organizing efforts. New organizing in retail and service took off like wildfire, as Starbucks workers waged a fast-moving campaign under the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Workers United wing; in the two years since they started their campaign, they’ve organized 360 locations. Those efforts inspired workers at smaller chains and independent restaurants and cafes to get organized, too. When a pizza place in my neighborhood organized with Workers United, the union election vote was unanimous.

“It’s hard to convey how popular the labor movement is right now,” Adam Conover told me. Conover, the creator of “Adam Ruins Everything” and “The G Word,” is a member of the WGA-West Board of Directors and served on the union’s negotiating committee for its minimum basic agreement. Throughout the writers’ strike, he was one of its public faces: on day one, he appeared on CNN and criticized the network’s owner, David Zaslav, for taking home $250 million in pay while writers rely on second and third jobs to make ends meet. On social media, he made videos explaining the issues at stake and the nuts and bolts of unionism to a public largely unfamiliar with them.

As Conover toured the country performing stand-up comedy to stay afloat during the work stoppage, he encountered overwhelming support, not only among his audiences, but from strangers, too.

“People see what we did as aspirational, as inspiring,” he told me. “It’s not ‘Hey, good job,’ but ‘Oh my God, maybe we can do that too.’ I hope that everybody in the labor movement is paying attention to that: there is an enormous hunger for this kind of organizing and for average people to use this kind of power.”

What accounts for this new feeling, decisively pro-labor sentiment in one of the Global North’s least labor-friendly countries? The US labor movement has been on the decline for decades, not just quantitatively, but qualitatively, too: less willing to go on the offense, more conciliatory than confrontational. In 2022, the unionization rate sat at a mere 10.1 percent: 33.1 percent in the public sector, and a measly 6 percent in the private sector.

There have always been exceptions to the story of US labor’s decades-long decline, pockets of resistance and rank-and-file fightback, but in 2023, the shift was unmistakable. The mood is restive, and not only among already-unionized workers.

“This is hard to prove, but the discrete bright spots that have always been there are starting to flow into each other,” labor historian Gabriel Wiannt told me. “The connections between these parts of the movement suggests that the power generated by distinct movements on the left and in labor is breaking out of the silos from where it originates.”

We always organize where we are, generating capacity and solidarity out of shared social contexts, with people we know; there’s no getting around that. But that’s a starting point, a limit which must be overcome. What, exactly, is allowing workers to begin overcoming it now?

The Impact of the Pandemic

The way the pandemic unfolded in the United States is the key factor. Covid spread with horrifying speed in workplaces–meatpacking plants, Amazon warehouses, nursing homes, restaurants and cafes–with low-wage workers hit hardest. In doing so, it made it impossible to disregard the differences between those who made money for their employers and the management and executives who retreated to remote work and second homes.

“The impact of the pandemic was to delegitimize management in all its aspects, good managers and bad managers: anyone in authority just could not protect the health or income of those they had before,” labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein told me. Faced with such differential levels of risk, it was hard to deny that bosses’ interests did not necessarily line up with the welfare of their workforce; often, their interests were in direct conflict.

So workers leaned on each other. As the labor market tightened, many people found themselves forced to work overtime well beyond what they had previously. In Starbucks cafes and Amazon warehouses, in Trader Joe’s supermarkets and food-manufacturing facilities, the pressure only brought them closer together.

Lichtenstein analogized the current moment to the post-World War II period, when workers underwent a collective experience extreme enough to rewire their view of the world. They expected more in the months after the war, and they were willing to fight for it.

“You’re coming off a period of economic disruption,” Lichtenstein told me. “We have a pandemic, they had World War II. New constellations of power and income are being worked out.”

The pandemic also lowered the stakes for the illegal employer retaliation that routinely follows union organizing efforts in the United States, where monetary penalties for such lawbreaking amount to mere pennies for major corporations.

“Enduring low unemployment and high turnover makes people not care as much about stepping out,” Winant told me. “Organizers are used to thinking of high turnover as a problem, and there’s a version of that which is true. But high turnover is also potentially a source of power, because it makes people feel like, ‘I don’t give a shit, I’m not going to be here in six months anyway.’ I’ve had workers say that to me.”

Or, as a founding member of the independent Trader Joe’s United union put it to me earlier this year, “I can find something else if need be–that’s part of where the lack of fear comes from. Being underpaid? I can get that elsewhere if I have to.”

Such a collective social experience, one in which the stakes could hardly be higher, is not easily forgotten, even if some of the uncertainty has declined and the labor market slackened (though it remains tight, with unemployment currently sitting at 3.7 percent). Said Winant, “People saw that the boss didn’t care if they died. Even if you’re no longer in that specific workplace, that experience stays with you.”

From Occupy to Bernie to the Present

Then there is what came before the pandemic. A throughline exists from Occupy Wall Street in 2011, the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns of 2016 and 2020, and the mass uprisings against police violence that peaked in the summer of 2020. While these movements are often counterposed, many workers in the United States participated in all of them, and were deeply shaped by the experience. Once one has spoken up against injustice in one arena, one does not leave that experience at the door when clocking into work.

When Sanders’s presidential campaign collapsed in 2020, many of his ardent young supporters took his message–of the power of unions, the centrality of the working class–and put it into practice. They became salts, taking jobs at workplaces they deemed strategic for labor organizing. Others enrolled in training programs geared toward employment in high-leverage jobs such as at UPS, or in socially important occupations like teaching and nursing. Others still become union staffers, or got involved in the myriad reform caucuses sprouting up in unions.

It’s important not to overstate the progress made thus far in labor’s offensive. In the wake of World War II, the period with which Lichtenstein analogized the present, more than 1.5 million workers struck simultaneously. Roughly 10 percent of the US workforce withheld their labor in 1946, in strikes encompassing some 4.6 million workers. Even in 1970, a moment far removed from US labors’ heyday, 3 million workers struck.

Petitions to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which oversees union elections in the United States, increased by 10 percent this fiscal year over the previous one, amounting to the highest number of petitions since 2016. Unfair labor practice (ULP) charges, which workers file with the NLRB when they believe an employer has violated their rights, were also up 10 percent over the previous year. Those are substantial increases, but nowhere close to amounting to a renaissance.

And further obstacles remain. Enterprise bargaining–organizing shop by shop rather than an entire sector or company all at once–is an agonizing process strewn with landmines in a country where labor law is wildly stacked in favor of the employer. While we currently have the most pro-labor NLRB in generations, which has demanded the reinstatement of workers fired for organizing and issued key rulings such as the recent Cemex decision, which says that if an employer commits a ULP that would necessitate another union election, the employer must automatically recognize the union instead–but we’ve yet to see whether workers can make use of those decisions to overcome employer scheming. And should we lose that labor-friendly Board after the 2024 presidential election, even these favorable rulings will become vulnerable.

Such context isn’t meant to dismiss the significance of the labor upsurge, but to put into perspective the extent to which workers in the United States have been disorganized, and the distance left to travel to build a fighting organized working class, one which reflects the demographic, economic, and social reality of US workers today.

The UAW on Strike

On September 14, the UAW struck the Big Three automakers simultaneously, the first time it has ever taken on the Detroit executives all at once. Fain announced the strike on Facebook Live, where he would go on to deliver regular updates throughout the work stoppage.

“I know that we’re on the right side in this battle,” said Fain during the broadcast announcing the strike. “It’s a battle of the working class against the rich, the haves versus the have-nots, the billionaire class versus everybody else.”

Rather than calling out all 150,000 members at once, the UAW engineered a new strategy, which it termed the “stand-up strike.” The name is a reference to the 1936 Flint, Michigan sit-down strikes that first forged the union, and the approach entailed an escalating wave of strikes: first at one major plant at each of the companies, then spreading to profitable parts-distribution centers.

The effect was military: when automakers failed to make meaningful progress at the bargaining tables, Fain would call up a new local, telling them that it was their turn to “stand up” and walk off the shop floor. Skeptics, myself included–I worried that such an approach might isolate those called upon to strike, undermining the unity among members that is so critical during a strike–saw the effectiveness: the approach allowed the union to keep turning the screws on the executives and generate media coverage with every escalation.

After more than six weeks, the union reached tentative agreements with all three automakers. The wins were historic: the restoration of cost-of-living-allowances given up during the Great Recession in response to the automakers declaring bankruptcy; the immediate conversion of legions of temporary workers into permanent status, and minimum 33 percent raises for legacy workers.

At Stellantis (formerly Chrysler), the UAW won the right to strike over plant closures and investment, as well as the reopening of an idled plant in Belvidere, Illinois. The latter was a priority for the union’s members, who had been scattered across the country when the company chose to shut down the facility in early 2023. And the UAW won a pathway to putting the companies’ electric vehicle (EV) plants under the Big Three contracts, an aim many had considered a nonstarter throughout the negotiations.

The workers didn’t win everything given up over decades of concessionary contracts–there are still members without pensions, and not every legacy employee is satisfied with their raise–but it was a decisive achievement.

“We’ve still got a lot of work to do,” Fain told me. “This was a great start and I’m very proud of the work we’ve done but there’s still a lot of work to be done in the future.”

Significant Growth in Union Reform Movements

Few of this country’s workers have seen evidence that they and their coworkers can win better lives through collective action. This cuts at a basic tenet of unionism, and the prevailing lack of such evidence has been a major obstacle to organizing efforts in the United States in recent decades.

Finally, with this year’s strikes and the decisive public support for each of them, that’s beginning to change.

“People supposedly participate in democracy, yet nothing seems to change because we’re living in a system of capitalism and money is controlling our politics,” Association of Flight Attendants- Communications Workers of America (AFA-CWA) president Sara Nelson told me, reflecting on the past year. “Now, people are looking at unions, and they’re seeing changes in one day, in a week, in as short as six weeks. That’s nothing compared to waiting years and years and being frustrated that nothing changes.”

“People started to see that they were struggling too much and that there had to be a better way,” Antonio Rosario told me. Rosario worked at UPS for more than two decades and is now a full-time organizer for Teamsters Local 804, which represents UPS workers in New York City. During the Teamsters’ preparations for what would’ve been one of the largest strikes in US history, Rosario was busy, connecting rank-and-filers across the company’s internal divides and preparing them for the possibility of a strike. That fight may be over for now, but there is plenty more work to do.

“Now that we all–in the UAW, in the Teamsters, and elsewhere–have these great contracts, we need to sit down with our workers and enforce those contracts,” Rosario said. “We know right off the bat that the minute the ink dries on these contracts, the company is violating them. That’s what they’re trained to do. So we have to train our workers to enforce the contracts, and while we’re doing that, we’re also making them organizers. All Teamsters should be organizers, all UAW workers need to be organizers. Everybody needs to learn to organize, because organizing is the lifeblood of our unions.”

Rosario is a member of the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), which inspired another key trend entering the new year: the rise of much-needed reform movements inside existing unions. TDU is one of the most longstanding such caucuses in the United States, and in the decades since rank-and-file Teamsters founded the organization, it has charted a path for other internal union reform work. TDU is working in coalition with the recently elected International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) president Sean O’Brien, and in doing so, has attracted a host of reformers from other unions eager to learn from TDU’s decades of experience.

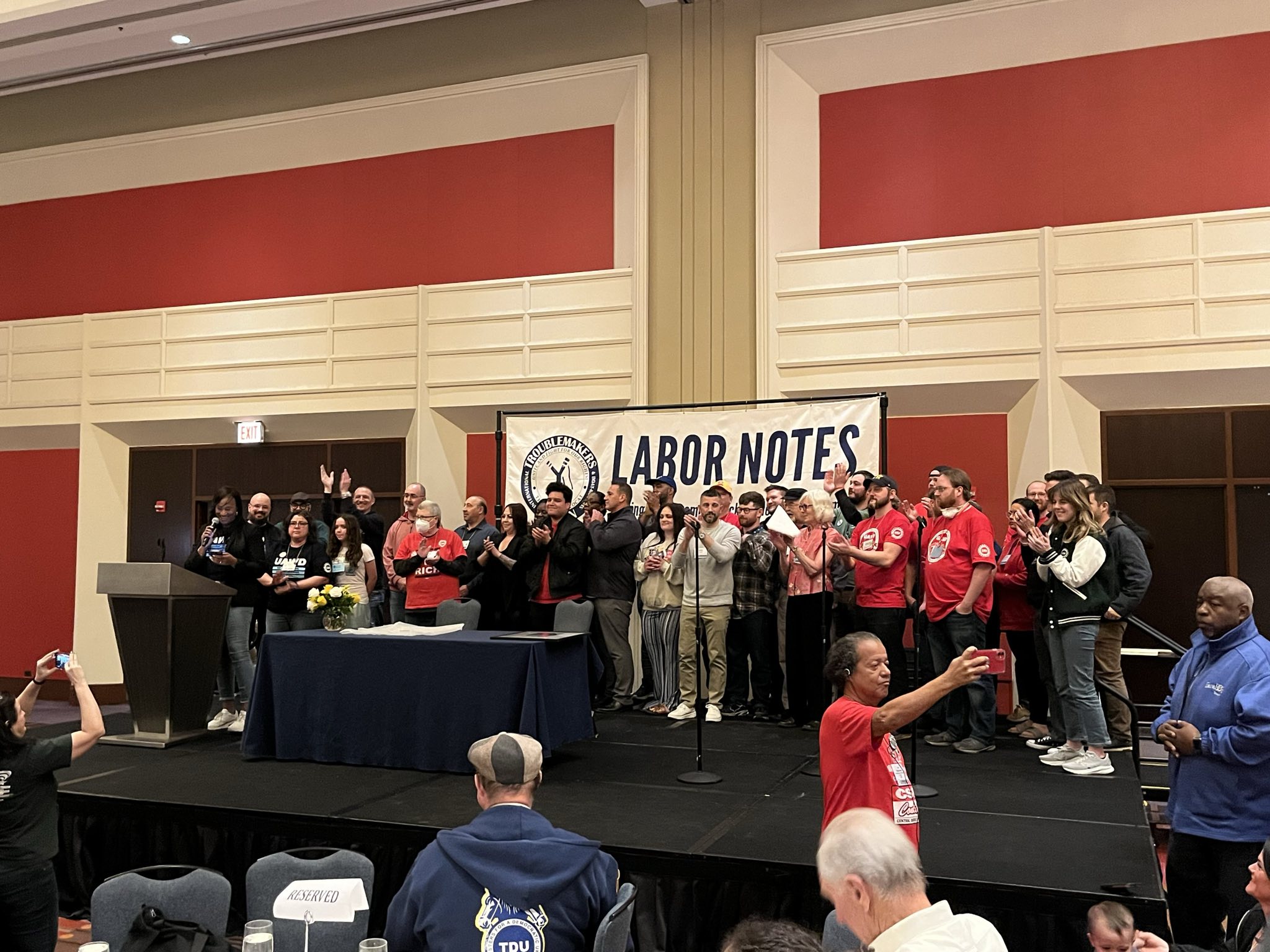

Such a growth in reform movements was on display at TDU’s convention this fall.

“When [Fain] said, ‘Without TDU, there would be no Shawn Fain. Without TDU, there would be no UAWD. Without TDU, there would be no stand-up strike,’ I was completely blown away,” Rosario told me.

Reform caucuses are now popping up in several of the country’s more staid, stuffy unions, those which have yet to embrace the democratization on the rise in the likes of the UAW. As Labor Notes’s Jenny Brown detailed in her own year-end reflection: reformers already have a significant base in the 1.2 million-member United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), and CREW, a new caucus, went public earlier this year in the 170,000-member International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). Rail Machinist reformers, too, are set to win an election in the 7,500-member District Lodge 19, which represents rail mechanics across the United States.

Such efforts reflect workers’ determination to not just win unions, but to democratize them in hopes of transforming the often lethargic institutions into fighting forces that can not only claw back concessions but go on the offensive in the political arena, pushing for changes that benefit both members’ broader communities and the entire working class.

Harnessing the power of the rank and file is central for those aims, the WGA’s Conover explained to me on a recent visit to New York, a rare vacation from union duties after a historic year.

“Our process is truly democratic,” Conover said of the WGA. “And we use that democracy to change our conditions for the better. We turned that democracy into power and we were able to force the companies to do what we wanted.”

“I was a neophyte, and now I’m a proselytizer,” he said of the power of democratic unionism.

What Happens Next

So after a landmark year for the US labor movement, what will 2024 bring?

In the short term, workers in some restive industries are preparing for key contract negotiations. In the airlines, there is strike preparation underway at United, American, and Alaska Airlines. The industry’s flight attendants want raises in line with those won by the UAW, as well as to address the strains created by the airlines’ scheduling snafus. And there is the campaign to organize Delta’s workers, a partnership between AFA-CWA, the Teamsters, and the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM)

“We’re also focused on scheduling parameters, ensuring that we’re paid for our work,” AFA-CWA president Nelson told me. “Flight attendants and passengers are getting stranded all over the place because the airlines haven’t invested in infrastructure in twenty years. They’re way behind.”

“Delta has been for nonunion decades: the pilots are unionized but not the stewards or ground people,” Lichtenstein, the labor historian, said. “They match wages with other airlines but the union’s doing a big push to get delta organized. If the AFA-CWA can organize that, that indicates something really has shifted.”

There are looming negotiations, too, for the entertainment industry’s other unions: both IATSE and the Teamsters’ Motion Picture Division have contracts with the studios which expire in July of 2024. The members who respected the WGA’s picket lines–and, in doing so, shut down the industry–will expect writers and actors to return the favor should a strike prove necessary.

“I hope that the studios are going to open the checkbook to IATSE and the Teamsters because they see how militant they are coming into negotiations, but the fact is, I’m not sure that’s the case,” Conover told me. “One of IATSE”s problems is that their workers are so tightly scheduled now because of the need to cut costs that people don’t have enough time to sleep. They literally are going home and sleeping for three hours a day for weeks on end. Does anybody at any of the companies understand that? Are they even willing to try to understand it? That’s what we’re going to find out next year.”

The UAW, fresh off its victory, has its sights set on the nonunion auto plants that now employ the majority of US autoworkers. The union is targeting thirteen nonunion automakers, aiming to organize some 150,000 of their workers, roughly the same number as are covered by its Big Three contracts. To ward off the offensive, some of those companies–including Honda, Toyota, Hyundai, and Subaru–have announced plans for significant raises. But it may be too little, too late; more than 1,000 workers at Volkswagen’s Chattanooga, Tennessee plant, which the UAW has previously tried and failed to unionize, have already signed union cards.

“I think the landscape is gonna change drastically,” Fain told me. “The sky’s the limit. To me, the determining factor is that working-class people have to decide, when it comes to elections and everything in life, what’s important to them. People care about being able to live; not scraping to get by.”

Alex N. Press is a staff writer at Jacobin covering labor organizing. Follow at @alexnpress.

Top Photo: AP Photo/Paul Sancya