In March, the United States Congress passed the bi-partisan Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to provide varying types of financial relief for businesses and individuals. However, sex workers and “prurient” businesses were excluded from receiving governmental assistance from this bill, adding to the economic stress already created by the pandemic. This led to the increase of sex workers turning to online work for income. As Elle reported, websites such as OnlyFans reportedly saw a 75 percent increase in sign-ups throughout April as unemployment rates skyrocketed. However, many street-based or outdoors sex workers did not have the privilege to simply mitigate the health risks associated with COVID-19 by not working or turning to virtual work. With some sex workers having fewer options to safely make money, many organizations have begun to prepare for potential long-term economic and health consequences on the community—particularly among Black and brown, trans, homeless, disabled, and street-based workers.

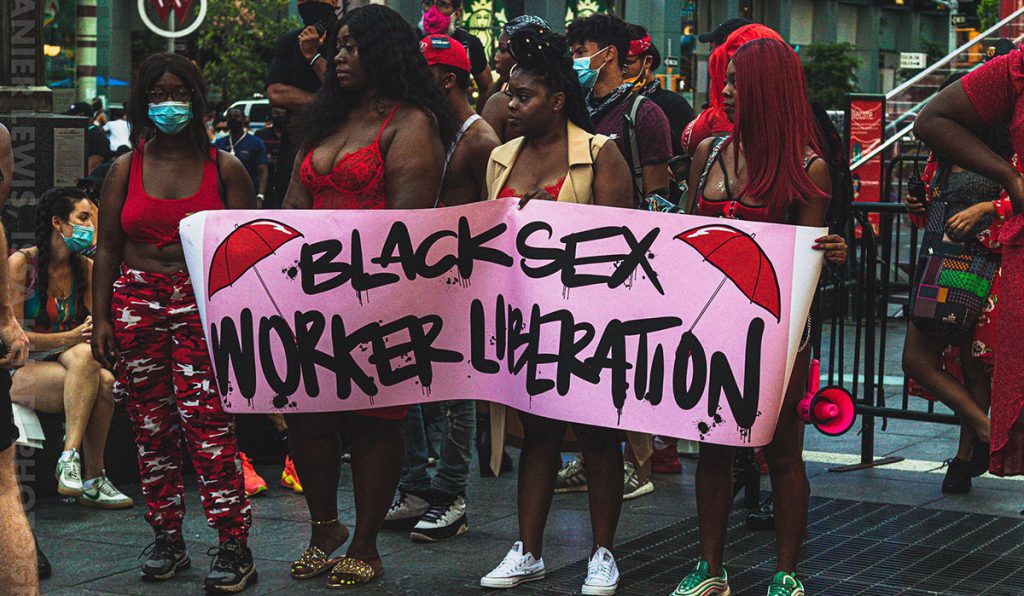

In response to the lack of governmental assistance, sex worker-led coalitions across the globe created or promoted existing local and national emergency mutual aid funds to provide direct cash relief to those in the community. While many of these funds were intended to be temporary during the beginning months of the pandemic, some have become semi-permanent resources due to the ongoing need for mutual aid. “We are still receiving requests, and have unfortunately had white sex workers posing as Black, disabled sex workers to ensure more cash relief,” Gassoh, a Volunteer Chapter Coordinator for Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP) Baltimore, says, noting that the organization has doled out cash relief to over 100 sex workers in Baltimore City since March. “With no rent relief and the eviction moratorium nearing an end, many sex workers may have to decide between homelessness, or living with family members or partners—some of whom may have a history of abuse,” she says.

Hazel, 32, a Salt Lake City-based sex worker, has been a recurrent recipient of SWOP Salt Lake City’s mutual aid fund since April. While Hazel and other sex workers have benefited from mutual aid funds, these limited payments barely cover the basic necessities needed to survive. “I was locked out of my apartment all the time when [the pandemic] first started. I’ve gone through a couple of hotels because we couldn’t keep up on the rent,” Hazel explains.

Though Hazel says business has picked up a bit, she only now is able to barely keep up with payments to remain housed. The current financial issues many sex workers are facing will likely have lasting repercussions. Tamika Spellman, a Policy and Advocacy Associate with HIPS, a Washington, D.C.-based harm reduction organization, says that, “There is the continuing problem of income disparity due to massive job losses in the public/private sector they were dependent on for their income.”

The financial insecurity some sex workers are experiencing has directly impacted some of the ongoing and arising health concerns since March. HIPS, which already provided an array of harm reduction services, housing and social services coordination, food distribution, counseling, and treatment options, increased health services in response to the pandemic.

“We do everything possible to provide whatever supplies we have to make staying healthy as easy as possible, to include what PPE we have and locally made hand sanitizer,” Spellman says. The organization also provides sex workers with information on current trends in the area and mandates “to assist in making safer choices.”

Many street outreach programs have also adopted new services like HIPS, handing out PPE materials, gloves, sanitizer, and resources on COVID-19. Some portions of the sex industry have reopened in more recent months, with added social distancing and health measures — such as strip clubs that require masks, and that dancers wipe down the stage area after use.

Despite the efforts from sex worker-led groups to keep people well, Hazel explains that some workers have abandoned using safe sex practices or personal protective equipment out of financial desperation. This led to her cutting off regular clients due to health concerns. “I think a lot of people are scared of the [coronavirus]. Some of them aren’t, but the ones that aren’t scared are the ones that scare me,” she says.

Unsurprisingly, Gassoh says that SWOP Baltimore has seen increased requests for STD kits from street-based workers, along with “more wounds related to client violence or drug use.”

In many ways, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sex work community is not dissimilar to the issues that emerged after the 2018 passage of FOSTA/SESTA, a bill that was intended to stop human trafficking by holding websites accountable for what users posted. Since its passage, research has found that the bill not only caused more harm to trafficking victims, but sex workers were subjected to more criminalization and violence. Just as crucial resources like Backpage were swiftly taken down following FOSTA/SESTA, Spellman, Gassoh, and other organizations have noted that many of the remaining sites that sex workers utilize to book dates with clients and screen them have been seized or taken down in recent months.

“Having the last few available online advertising spaces disappear recently has made it much harder to stay safe within your own home, and maintain a satisfactory income to survive without returning to street based sex work where the risk of COVID-19 is the number one concern, [and] then the potential of aggressive policing of sex workers and clients,” Spellman explains.

Furthermore, Gassoh explains that increased criminalization puts sex workers at risk of being exploited, because “the lack of aid from the state/federal government creates precarious conditions for trafficking people into forced labor — like the sex trade.”

In Salt Lake City, Hazel has noticed law enforcement is beginning to become more aggressive, and she echoes the concerns that have been shared by Gassoh and Spellman about losing her ability to provide for herself. “If we have to leave the hotels, what are we supposed to go? The streets? If it comes to that, I’m not going to have a way to make money,” she says in an exasperated tone. “If we have to quarantine, I don’t know what we’d do.”

With the growing safety and financial concerns, sex work organizations are not only worried about the physical health of their peers, but their mental wellbeing for years to come. “The potential for trauma is a huge possibility, along with long-term anxiety and mental health issues,” Spellman says.

Like past legislation and ongoing criminalization, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented new barriers to sex workers simply trying to provide for themselves, to survive, and to receive healthcare or housing. However, the sex work community is, and always has been, resilient. We show up for each other time and again, and our community will persevere as we empower and support one another.

Kyli Rodriguez-Cayro is a Cuban-American writer, mental health educator, and sex work activist based in Salt Lake City.